Dr Matthew Francis and Dr Christopher Hill reflect on a disastrous general election night for Labour and the Liberal Democrats.

Dr Matthew Francis, Teaching Fellow in History

On Labour:

There are three widely discussed reasons that Labour have lost, and I think there’s also a fourth one that the party need to think about.

There are three widely discussed reasons that Labour have lost, and I think there’s also a fourth one that the party need to think about.

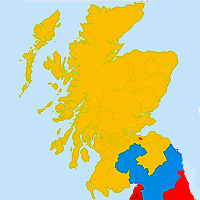

The first of the three obvious reasons has to do with Scotland – the fact they’ve lost so many seats to the SNP in Scotland and haven’t been able to put up much of a fight there. The second is Miliband’s leadership, which has been questioned for a long time but looked during the course of the campaign like it was getting better and he was becoming more trusted by the electorate. That’s clearly not worked out in practice. The third of those widely discussed issues is economic confidence; that after the 2007-2008 financial crisis and after the deficit grew so large, voters didn’t trust the Labour party to get the economy back in order and get spending under control.

The fourth reason is potentially more significant, and it has to do with culture. If you look at the seats that Labour have lost overnight – John Denham’s seat in Southampton; Ed Balls’s seat in Leeds – the reason they lost those seats isn’t necessarily because the Conservative vote has improved but because the Ukip vote in those seats has improved. Labour look to have lost quite a significant amount of support to Ukip, and that suggests there’s a cultural thing going on; that actually the Labour party is struggling to connect with disenfranchised, disconnected, working-class electorates – the kind of people who ought to be Labour’s core support but this time seem to have turned out for other parties.

On the Liberal Democrats:

Obviously part of the reason the Liberal Democrats have performed so poorly has been because of their involvement in the coalition. For a long time, the party really sold itself as an anti-Conservative party – after the 1992 general election Paddy Ashdown gave a speech in which he said that the Liberal Democrats had to openly come out as an anti-Conservative party and work with the Labour party to ensure that there wouldn’t be another Conservative government. A lot of the votes and a lot of the seats they won after 1992 were built on the back of that. Of course, if you run an anti-Conservative strategy and then go into coalition with the Tories, you are inevitably going to be punished for that by the electorate.

Obviously part of the reason the Liberal Democrats have performed so poorly has been because of their involvement in the coalition. For a long time, the party really sold itself as an anti-Conservative party – after the 1992 general election Paddy Ashdown gave a speech in which he said that the Liberal Democrats had to openly come out as an anti-Conservative party and work with the Labour party to ensure that there wouldn’t be another Conservative government. A lot of the votes and a lot of the seats they won after 1992 were built on the back of that. Of course, if you run an anti-Conservative strategy and then go into coalition with the Tories, you are inevitably going to be punished for that by the electorate.

There’s a second problem for the Liberal Democrats, though, which is that many of the seats they won in that period were in Conservative marginal seats – they won those seats from the Conservative party, not from Labour. The result of that is that as the Conservative vote has increased, the Liberal Democrats have lost those seats. A lot of the voters who went to them during the 1990s and 2000s have gone back to the Conservatives, and as a result they’ve lost votes on both sides – anti-Conservative voters who felt betrayed after 2010 have gone back to Labour, and ex-Conservative voters who now feel more content with their party.

Dr Christopher Hill, Teaching Fellow in History

On Scotland:

It’s fascinating to see what’s been happening in Scotland, and I think this is going to transform the political faultlines in Britain. What’s so amazing about it for me, as a modern historian, is to see so many of these Labour strongholds go. Seats that the Labour party have had and tried to nurture from the 1920s, all the way back to the days of Ramsay MacDonald, are now lost. What this means for British politics is going to be very interesting – not just in relation to Scotland but for the whole of Britain. Quite clearly, with the Conservative majority that’s coming through, David Cameron is going to have to respond very quickly – maybe we’ll see a situation where ‘devo max’ is granted. How that then impacts on England is also going to be fascinating, because that’s going to push forward the agenda for English votes for English laws. So this really is a huge moment in modern British politics.