Alan Keen was an antiquarian bookseller, who ran his business from the Gate House of the old Clifford’s Inn in London. It was June 1940 and Britain was at war with Nazi Germany and suffering under the Blitz. ‘When the sirens wailed’ wrote Keen, ‘my little staff and I went underground – often carrying our work with us, for the cellar had one useful electric bulb to relieve the gloom.’

On this hot summer day, however, all was calm, and Keen and his assistant were making a quick examination of the contents of a country library which had just been purchased. In the course of sorting and separating the haul of centuries old books, a thick and shabby folio volume came to hand. Keen settled down to examine it in the cool of his office, not knowing that he was starting a detective story which would attract the interest and attention of generations of scholars.

Alan Keen examining marginalia through a magnifying glass

The volume was a copy of the Chronicle of Edward Hall or, as part of the opening fanfare read, The Union of the two noble and illustrate families of Lancastre & Yorke. Hall (1542 – 1547) was a lawyer and historian, who had developed a lifelong interest in recording the events of English history. His Chronicle was published in 1548 with a revised edition appearing in 1550. It covered the Wars of the Roses and the rise of the House of Tudor, beginning with the accession of Henry IV in 1399 and closing with the death of Henry VIII in 1547. As a record of spectacle, revels, ceremony and performance at the Tudor court it was invaluable, providing particular detail of the reigns of Henry VII and Henry VIII.

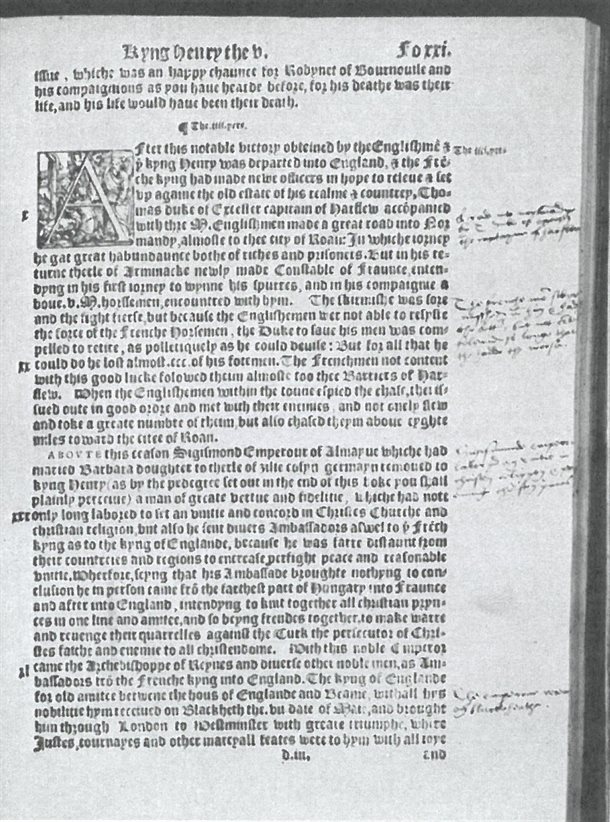

Keen noted that the title page was missing, and that the volume lacked a further page at the beginning. Several hundred annotations, many of them in commentary on the reigns of Henry IV, V and VI appeared in the margins. An earlier owner had had the book cheaply rebound, which effectively shortened the margins and destroyed parts of the handwritten notes. But still there was material amounting to around 3,600 words, or 406 marginal notes as well as crosses and underlinings. In historical terms, these added the unique testimony of a contemporary perhaps, or even of an eyewitness. In literary terms, the Chronicle covered the period often written about in Elizabethan literature: most notably in Shakespeare’s history plays.

Annotated page from Hall’s Chronicle

Annotated page from Hall’s Chronicle

Shakespeare is known to have used Hall’s Chronicle as source material, though Holinshed’s mighty tome was his major source of information. Keen, however, was excited by the fact that the majority of annotations were focused on Hall’s account of the reigns of Henry IV, Henry V and Henry VI. A new thought came to mind and he commented:

‘It seemed odd to me, a bookseller, that so unsatisfactory a copy…should be preserved when rare books in perfect state were as plentiful as blackberries…I began to decipher the handwriting and to study the notes in relation to the text. They did not seem those of a casual commentator.’

He now attempted to establish the age of the annotations. An expert at the British Museum Research Laboratory made a forensic examination of the volume and concluded that the notes were of considerable antiquity and were probably all made at the same time. The writer then, was a contemporary of Shakespeare, and whatever other tempting ideas were bubbling up in Keen’s mind, he now referred to him as The Annotator or A.

A’s notes appeared to be the signposts left by a thoughtful and methodical reader whose purpose was to learn and inform himself. Keen noted examples where A’s choice of Hall’s words is repeated by Shakespeare and where a detail or expression is selected from Hall and used verbatim, or in the same general sense. Shakespeare also gives dramatic expression to certain passages in Hall by stylistic features such as rhetoric, oration and lively narrative detail. Verbal echoes of the Chronicle occur frequently, suggesting that A had read the material carefully enough for some words to linger in his memory.

The handwriting of A was also compared with the accepted signatures of William Shakespeare, but these are erratic in form, so to determine the nature of the poet’s handwriting was not possible, other than the fact that he used the cursive hand common in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

All this close research inevitably raised questions: were A and William Shakespeare one and the same? Was this Shakespeare’s workbook? If so, where was Shakespeare when the marginal notes were made and where was the book if and when Shakespeare did make them?

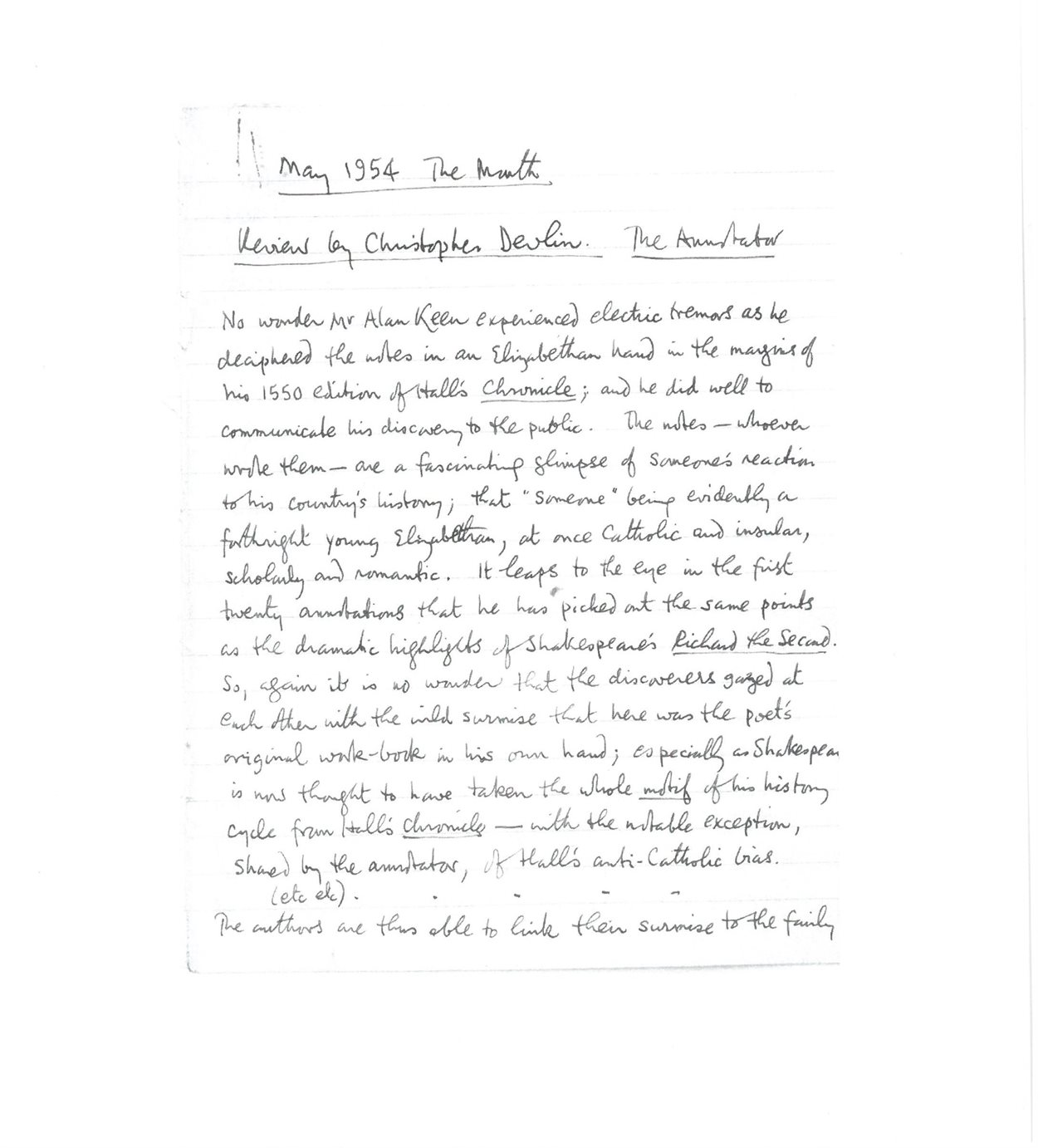

Handwritten review by Christopher Devlin of of Keen’s book, The Annotator, dated May 1954

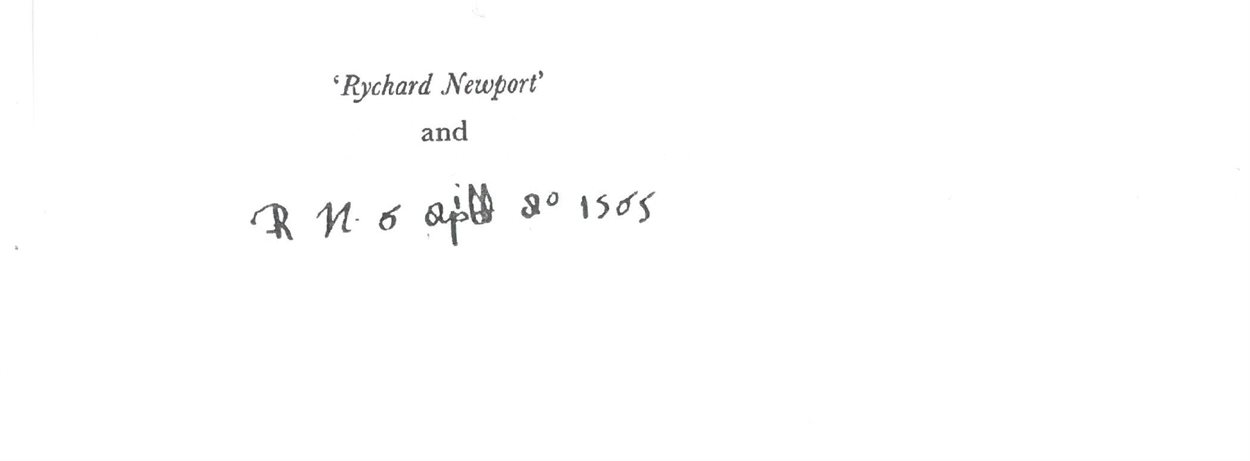

Among the Chronicle’s annotations was a signature of ownership – that of one Richard Newport. It appeared twice, in a hand completely different from that of the Annotator and many pages after the annotated part of the volume. On another page Newport had put his initials and the date: 6 April 1565. It was another clue in the detective story, though frustratingly, inquiry turned up two men of that name: contemporaries, living in the sixteenth century. One of the Richard Newports was eliminated when his signature did not match that in the Chronicle. Keen had little hope of discovering the other Richard Newport until he investigated the family records and noted the close connections, by marriage, of the Newport line with the families of Houghton and Hesketh.

The Richard Newport signatures

The Richard Newport signatures

These names, occurring together in a family tree, reminded him of a document discussed and described by earlier critics. This was the last will and testament of Alexander Houghton (1581), a gentleman of considerable property who lived at Lea Hall, near Preston, Lancashire. It left to his brother Thomas ‘all my Instrumentes belonging to mewsyckes and all maner of playe clothes'. It also made mention of Ffoke Gyllome and William Shakeshaft, two servants who were part of Houghton’s household, asking that they should receive ‘ffrenddlye’ treatment and be taken into the service of the new master, if they so wished.

What had jogged Keen’s memory were the old stories about Shakespeare’s ‘lost years’: that yawning gap between 1585, when the birth of his twins was recorded in Stratford-upon-Avon, and 1592 when the London dramatist Robert Greene identified him as a pushy newcomer in London’s new theatreland. Among various anecdotes about what Shakespeare was doing in those seven years - ranging from the plausible and possible to the fanciful and outrageously unlikely – John Aubrey in Brief Lives of 1681 had claimed that Shakespeare was a schoolmaster in the country for part of the ‘lost years’.

The topic remained unaddressed until a twentieth century scholar suggested that Shakespeare might indeed have worked as a tutor for a wealthy Catholic family in Lancashire. But why had he turned up in that particular area? The question recalled evidence that the Shakespeare family of Stratford-upon-Avon were secret Catholics in a country where Catholic ritual had been made illegal. The Houghtons were Catholic and wealthy, among a number of other Catholic and wealthy families. To join such a household might well provide security from the law and allow a young man to practise his religion freely.

It also provided fertile soil for an emerging playwright for, if the ‘playe clothes’ of Alexander’s will were actually stage costumes, it indicated that he kept ‘playeres.’ This was quite often the case among noblemen whose various bands of players ranged the country but did so under the protection of their lord or patron. It takes only little imagination to suggest that the William Shakeshaft of Houghton’s will was the young William Shakespeare from Stratford-upon-Avon, operating under a partial alias, and learning his craft as a member of Houghton’s troupe.

There are mountains of speculation relating to the seven years after Shakespeare drops out of the official records in Stratford-upon-Avon before reappearing as actor and playwright in London. The work of Alan Keen adds a strand of credibility to the story that he lived in Lancashire and there, perhaps, lost himself in a copy of Hall’s Chronicle one day, scribbling in the margins.

Debate and theorising continue: there were many Shakeshaft families in the Preston area, and some scholars suggest that Shakeshaft and Shakespeare were interchangeable names and that the young man from Stratford had become known by the local variant. But whoever Shakeshaft was, he might equally have been a local man, born and bred in Lancashire and older than the teenage Shakespeare. Other commentators cling to the theory that Shakespeare’s Catholicism took him to Lancashire where, among Houghton’s ‘playeres’, he began to develop as a dramatist. Only proof was lacking.

Keen’s work illuminates the link between Shakespeare’s source material and some of his history plays, though the exact identity of the Annotator of Hall’s Chronicle remains to be established. It was a fascinating coincidence that he also uncovered material that might add to the ongoing inquiry into Shakespeare’s ‘lost years.’

Keen was well aware that what he had discovered could form only a small part of the biography of Shakespeare. At the end of his book, The Annotator, he humbly offers his research to the wider world of scholarship:

‘any writer must take old threads and bring to them the bright new skeins, spun by the industry of contemporary scholars on both sides of the Atlantic…. For the tale is by no means told. The compass of the present book can only take in pointers to the material for further explorations.’

Those ‘bright new skeins’ have not been lacking.