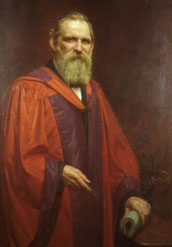

1842-1920

Charles Lapworth was born in Faringdon, Berkshire and trained as a school teacher in Oxfordshire, his main interests at that time being literature, history, art and music. His first post, in 1864, was in Galashiels and in 1875 he was appointed to Madras College in St Andrews. Lapworth’s interest in geology started shortly after his move to Scotland and, although largely self taught in the subject, he soon began to make significant contributions towards unravelling the geology of the Southern Uplands.

Charles Lapworth was born in Faringdon, Berkshire and trained as a school teacher in Oxfordshire, his main interests at that time being literature, history, art and music. His first post, in 1864, was in Galashiels and in 1875 he was appointed to Madras College in St Andrews. Lapworth’s interest in geology started shortly after his move to Scotland and, although largely self taught in the subject, he soon began to make significant contributions towards unravelling the geology of the Southern Uplands.

Lapworth recognised the importance of the graptolite fossils within the rocks of the Southern Uplands, and how they could be used to zone and correlate the sequences across the area. He realised that in order to record individual rock units, and associated graptolite biozones, the area had to be mapped in great detail. He pioneered the use of detailed, large-scale geological mapping, which proved vital for the interpretation of the geological structure and history of the region. His work resulted in the Geological Survey having to re-map and re-interpret the entire area, and producing in 1899 the great Memoir on the Geology of the Southern Uplands of Scotland which has been described as 'a monument of the man [Lapworth] who made it possible'.

Lapworth's understanding of the Lower Palaeozoic rocks of Great Britain and Ireland led to his resolving of the great Cambro-Silurian controversy in 1879. The division, and boundary, between Adam Sedgwick's Cambrian System and Sir Roderick Murchison's Silurian System had been argued for many years. Lapworth resolved the issue by clearly demonstrating three distinct Lower Palaeozoic faunas. He used these to divide the Lower Palaeozoic into three stratigraphic units - the Cambrian System (oldest), a middle System that he named the Ordovician, and the Silurian System (youngest).

By the late 1870s he had a significant academic reputation and in 1881 he was appointed as first professor of geology at Mason College, the forerunner of the University of Birmingham. As his first research project at Birmingham, Lapworth chose to re-examine the geological structure of the Northwest Highlands which had been the source of great controversy. In the summer of 1882 he began mapping in Durness before moving on to Eriboll, labouring both day and night, and had essentially solved the NW Highlands problem by the end of that season. Lapworth was familiar with the latest research of Heim and Suess in the Alps, and realised that the superposition of metamorphosed gneiss and quartzite on top of limestone was due to complex, contractional folding and faulting - in short, it was due to what we would now call thrusting.

Lapworth returned to the Loch Eriboll area in the following year, but the excitement of solving the fifty-year-old controversy seems to have been too much for him. He had a severe illness, at least in part of psychological origin, and his sleep was much disturbed by nightmares. He was, however, able to publish his preliminary results in the Geological Magazine (1883) under the evocative title 'The secret of the Highlands'.

Lapworth returned to the Loch Eriboll area in the following year, but the excitement of solving the fifty-year-old controversy seems to have been too much for him. He had a severe illness, at least in part of psychological origin, and his sleep was much disturbed by nightmares. He was, however, able to publish his preliminary results in the Geological Magazine (1883) under the evocative title 'The secret of the Highlands'.

Having taken up residence in Birmingham, Lapworth spent many years studying the rocks of the Midlands and Welsh Borderland, becoming the leading authority on the geology of the area. Much of his free time was spent taking groups including students, amateur and professional geologists, and natural history societies, on field excursions within the region. He made important discoveries of Lower Cambrian fossils at Comley near Church Stretton in Shropshire, and at Nuneaton in Warwickshire.

Lapworth's research on the graptolites, which began during his work in the Southern Uplands of Scotland, continued throughout his career and he became world renowned as the foremost authority on this extremely important fossil group. He published numerous and important scientific papers on this group of fossils culminating in the Monograph of British Graptolites which he edited, and assisted geologists worldwide with the identification, dating and interpretation of graptolite faunas.

Lapworth also carried out important applied and economic geological work particularly in the Midlands region, making significant contributions to the Royal Commission on Coal in connection with the Midlands coalfields. He was also active in engineering issues and water resources work for large areas of the Midlands region.

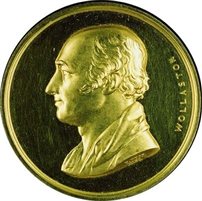

Lapworth received many awards for his pioneering work and contributions to geology. In 1891, he received the greatest scientific accolade when presented the Gold Medal of the Royal Society. While in 1899, he received the highest award of the Geological Society of London, the Wollaston Medal, in recognition of his outstanding work in the Southern Uplands, and Northwest Highlands of Scotland. The Lapworth Archive, housed in the museum, contains a remarkably complete record of all areas of his research work and teaching.

Lapworth received many awards for his pioneering work and contributions to geology. In 1891, he received the greatest scientific accolade when presented the Gold Medal of the Royal Society. While in 1899, he received the highest award of the Geological Society of London, the Wollaston Medal, in recognition of his outstanding work in the Southern Uplands, and Northwest Highlands of Scotland. The Lapworth Archive, housed in the museum, contains a remarkably complete record of all areas of his research work and teaching.