In Conversation: Perspectives on Art Interpretation

Museum Learning Officer Brian Scholes and Lecturer in Art History Sophie Hatchwell discuss the similarities and differences between art interpretation in the public gallery and in the lecture room, focusing on pieces from the collection of the Herbert Art Gallery & Museum.

- Brian Scholes and Sophie Hatchwell

- Collection: Herbert Art Gallery & Museum

- Download a PDF of this article

- Keywords: Sir Thomas Lawrence, Joan Eardley, Ben Nicholson, art interpretation.

Our article is a conversation about the different ways art can be interpreted. It explores the similarities and differences between two approaches – that of Lecturer in Art History, Sophie Hatchwell, and Learning Officer for Schools, Brian Scholes. We compared and contrasted our interpretations of three works of art from the collection of the Herbert Art Gallery & Museum, Coventry, where Brian is based. When we began talking about art interpretation, we were interested in discovering whether there were any overlaps in our approaches, and what we could learn from one another. Writing to each other over a five-month period, we were initially struck by two key common threads. First, the huge benefit to be gained from studying works in person, and the way in which close observation can shape our understanding. Secondly, the role that narrative and story can play as interpretive tools, both historical, but also more imaginative and creative narratives too. These can fuel our thinking and encourage close looking and comparative analysis in turn. This article presents extracts from our conversation, where we discussed three paintings: Sir Thomas Lawrence's Portrait of King George III (fig.1, 1792), Joan Eardley's Glasgow Boy with Milk Bottle (c.1948) and Ben Nicholson's 1946–47 (two forms) (1947). The conversation shows us learning about each other's practice, reflecting on our own approaches, becoming more self-aware about why we do what we do, and deepening our understanding of the paintings by learning from each other's interpretations. We hope that this article will encourage our readers to look at art works in different ways. We want to move away from the assumption that there is only one right way to look at and interpret a work, and instead celebrate the ways in which creative and heterogeneous approaches to interpretation can lead us to see new details in art works and raise new questions about how we read and interpret them.

Sophie Hatchwell (SH): When we first met in the gallery we looked at two portraits: Sir Thomas Lawrence's King George III, and Joan Eardley's Glasgow Boy with Milk Bottle – I've been thinking about our interpretations of these works and there's a lot to say!

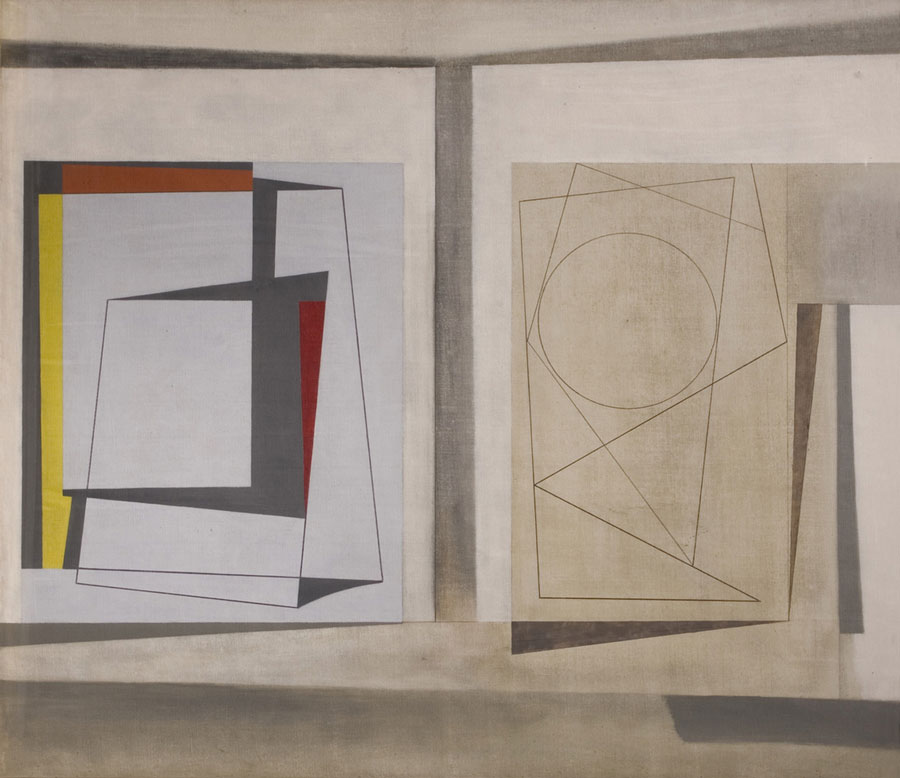

Fig.2 Ben Nicholson, 1946-47 (two forms) (1947), © Angela Verren Taunt. All rights reserved, DACS 2019. Image courtesy of Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Coventry.

Brian, you mentioned the things you talk about with your educational groups and I remember you saying you got schoolchildren to think about the function of portraits, particularly in relation to what the paintings can tell us about the people in them – their expressions/feelings, and their identity as portrayed through dress and surroundings.

A royal portrait such as that of King George III provides rich material for art historical exploration of identity, but what strikes me, about both this work and Eardley's Glasgow Boy with Milk Bottle, and perhaps emphasised because they come from such very different historical and artistic contexts, is what they tell us about the artist – why the artist chose to paint them, whether we can recover anything of the artist's intentions, and whether through simply looking at the paintings themselves, we can see any evidence of the artist's presence.

Starting with the Lawrence portrait, the following springs to mind:

Lawrence (1769–1830) was a Royal Academician, elected as an Associate in 1791, an early moment in the history of the Royal Academy (RA), which was inaugurated less than twenty-five years previously (1768). The RA's function was in part political, to signal the cultural sophistication of Britain and fuel the country's international prestige. On a socio-economic level, it also marked a shift in the status of member artists – membership signalled them to be at the same time both gentlemen and professionals. The RA was, of course, also patronised (and instigated) by the King, providing an additional level of status and recognition for these artists.

Lawrence was only 23 in 1792, when the portrait was made. He had come from a fairly humble background (son of a pub landlord I think) and was self-taught as an artist. The fact that he paints the King, suggests he is also making a statement about his new-found status – a professional painter, member of an elite body of artists, and now a gentleman: patronised by the King and circulating with other gentleman of culture through the circles of the RA and court [1]. The scale and grandeur of the painting of George III not only glorifies the King but reflects back on the artist as well.

How does this focus on the artist fit in with the interpretive work you do with your educational groups? Also, I'm really interested to hear more about your learning programme.

Fig.1 Thomas Lawrence, Portrait of King George III (1792), © Courtesy of Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Coventry.

Brian Scholes (BS): To answer your latter question first – learning sessions are themed, so we deliver different workshops around paintings, sculptures and prints. We also run a storytelling workshop which uses a variety of artworks from different genres – this includes quite a lot of role-play which is good fun! Workshops are largely aimed at Key Stage One (ages four to seven) and Key Stage Two (ages seven to eleven). The workshops always include a practical element (such as sketching from original works of art, making sculptures out of clay, or block-printing). Additionally, we give talks and tours for older students.

One of the main benefits of the workshops is that children get to see original works of art first-hand. Furthermore, making sketches from these gives the pupils a prolonged period to properly engage with the art. For one thing, getting so close to an original work of art enables the pupils to see differences in artistic styles which wouldn't be as obvious from looking at secondary source images. Using the Thomas Lawrence/Joan Eardley (1921–63) paintings as examples – both artists, obviously, have different techniques (Lawrence is realistic, Eardley expressive) and so actually seeing the brushstrokes (or not, as the case may be) helps to compare and contrast the artists' approaches.

Other comparisons can be made by viewing the originals, such as scale – the very large Lawrence painting compared to the relatively small Eardley work ('why is the King so large and the boy so small?' is a good discussion point).

Another benefit is that as each workshop has a practical element, pupils get the opportunity to use original works to inspire their own art practice. This is true for sketching (which I've mentioned) and also for the sculpture and printmaking workshops where pupils get to create sculptures and produce their own prints respectively.

Going back to your first question: the alternative interpretation of King George III being (also) about Lawrence as an artist does have some relevance with our educational groups, for example, I like to talk a little bit about the artist, particularly the story about how Lawrence was from a humble background and his talent was such that he was elevated to a very high position indeed in a relatively short space of time. However, my main focus is on the portrait itself and the King.

With older students, I will touch upon the historical events of the time and how this has a bearing on the painting – the French Revolution had occurred just three years prior to the portrait being produced and there is symbolism within it to suggest that the picture is intended as a rallying call to inspire support for the monarchy (the Order of the Garter which the King wears, for example).

I am very interested to find out your thoughts on the Eardley painting to see how our approaches compare and contrast.

SH: With the Eardley portrait, we have to be more speculative I think.

We can perhaps say something about the appeal of the subject matter for the artist. I know there has been a recent exhibition of her work in Edinburgh and I wonder whether the scholarship arising from this says anything about her interest in depicting childhood poverty in Glasgow. We can comment on the fact that these are the sort of everyday scenes she would encounter in areas of Glasgow, where she trained and lived, during the post-war era slum clearance.

For me, however, the most interesting thing about Glasgow Boy with Milk Bottle is the way colour and paint seem to be a marker of the artist. There's much in the painting that doesn't make sense as naturalism, which suggests the artist is using colour to make us think in a particular way.

The main example of this for me is that we look at this image of the boy, with a retreating figure behind him, and immediately assume this is his mother walking away from him. But why do we identify this figure as a mother, or think that the boy has been left behind? I'm drawn by the colour. The purple colours of the lower half of the boy's figure blend into the similar colour of the surroundings and the grey-blue tones of his torso blend into the background. Compositionally, colour divides the image in a corresponding way across both foreground and background, suggesting the boy is disappearing into his surroundings: forgotten or cast aside.

Then there are two additional notable bits of colour: the smudge of blue on the boy's cheek and white of the milk bottle. The white draws a link between the figure of the boy and the colour of the retreating figure's clothing. Perhaps we are being asked to associate the milk with the retreating figure, and with this in mind, there are a number of arguments to be made as to why this would then cast the figure as the mother. We are also encouraged to look at the boy's feet – bright white like the milk, and comparable to the retreating figure's legs. The colour of the figure moving away is less bright – as if in shadow or retreating, the shape of the feet less clear. This is in contrast to the solid fixity of the boy's white feet. Perhaps we are being asked to see movement/retreat contrasted to immobility.

It seems that through this artificial manipulation of colour and form, the artist is effectively guiding our reading of the work. To me, it is the inclusion of the smudge of blue that shows the artist revealing her hand here. It bears no logical relation to any other aspect of the painting. Therefore, it seems like a deliberate act on the part of the artist, not something representational but simply a record of a gesture of the artist putting paint on canvas that says to the viewer: 'I am here and I am making this work'. There have been other examples of artists doing a similar thing; including an inexplicable visual detail that isn't representational but instead seems to just identify and draw attention to the hand of the artist [2]. So for Eardley, this is not simply an objective observation of a child, but her own personal reflection on what she's seen.

I see that this focus on the artists may have limited relevance with the sort of interpretive work you do with your younger educational groups, but is there any scope for this with older students?

BS: Yes, indeed – your alternative interpretations do have relevance to older groups (which I will come on to later), but actually – in the case of Eardley's work – with younger groups too. I found your interpretation of Glasgow Boy with Milk Bottle particularly fascinating. When I introduce this painting to groups of younger children I usually ask them who they think the retreating figure is, and nine times out of ten the response will be the mother of the boy. Your connections of colour around the milk bottle and figure retreating further add to my assumption (and belief) that this is the mother. The image of the woman walking away adds to the plight of the child, yet the figure (or semi-figure) is actually just a series of simple abstract shapes. I think the genius of Eardley is that she can evoke such a powerful scene of heartfelt emotion, through such basic imagery.

Your other observations regarding Eardley's use of colour are certainly aspects I explore when discussing the painting with children. The dark and muted hues that are used to great effect in creating feelings of despair and neglect, for example. The blue smudge you refer to is often interpreted by children as being a teardrop. As you say the blue bears no logical relation to the rest of the painting therefore your belief that this is Eardley 'showing her hand' is a strong assertion, and would make sense (for the purposes of Key Stage One and Key Stage Two I tend to go along with the teardrop idea – although in reality it would be a little too obvious, and frankly, at odds with the subtleties of the rest of the painting had the artist literally meant to show the boy crying).

Coming back to the older students (Key Stages Three, Four and Five), I would emphasise the historical context of the work. Eardley's painting can be viewed as a social commentary on post-World War II poverty. I believe both she and Lawrence use their portraits to illustrate aspects of their respective times.

By the way, I also include the Lawrence painting in the storytelling workshop, 'Stories in Art'. This workshop uses artworks as objects to help to tell stories. The session (as previously noted) includes lots of role-play, and I often use traditional myths and legends where there are heroes and anti-heroes. For example, the Lawrence would be used if a story included a king – while the king in the story is unlikely to be George III, the portrait helps to set the scene and tell the tale. Within Stories in Art, I would use a number of artworks and objects including portraits, landscapes, abstract paintings and sculpture – thus introducing children to a wide range of art.

Your interpretations of Glasgow Boy and George III have inspired me to include some of your ideas in gallery tours, particularly for older students. Your previous comments about Lawrence and his new-found status as elite artist would provide a good talking point in relation to the 'role' of the artist and how artists have been viewed at different points in history. Similarly, your assertion of Eardley ';showing her hand' as an artist with the blue smudge, is frankly something I wouldn't have thought about but I can definitely see this as being an interesting talking point.

SH: It's good to see how our respective approaches to the Eardley piece come together so well! I fully agree with your point that portraits are in many ways a reflection of their own time. Perhaps we can think of it being a portrait of a moment in time, as much as of a person. I wonder how people's responses to the works might change if they were initially introduced in this way.

I'm very interested in how you use story and role-play in your educational activities. When we started this conversation, I was thinking about biographical narratives about artists or the subjects of portraits, but I see you take a much more imaginative approach.

In art history in higher education we tend to fixate on interpretations that can be evidenced (by reference to historical context, other art historians'; readings, formalist and iconographic analysis etc.), and often overlook the value of taking a more creative approach. I'm beginning to do this with some of my post-graduate students, where we pair art works with things like poems and novels, but it's something I'm still working on and thinking through – so I think I will say more later.

For now, I would like to know more about your use of story and role play as a form of interpretation. When we met in the gallery I remember you talking about using Ben Nicholson's 1946-47 (two forms) in this way, so can I ask you to tell me a little about this? Also, how do you select what stories to present, or perhaps I should ask, how do you select which art works you will use as prompts for stories?

BS: To select art works to use as prompts for stories, the main thing is to see what there is to work with (artefacts/objects) then choose a story that could include a variety of these. Also, it is a good idea to choose stories appropriate to age both in terms of content and in terms of delivery time (it would be better to keep stories for the very young quite short, for example).

As I've previously mentioned, the session includes a lot of role-play (often with costumes and props). I talked about Lawrence's portrait as being a favourite here – other artworks might include landscapes (to help recreate the idea of a location), sculptures of people (for individual characters) and even abstract pictures that can be used in a variety of creative ways to form part of a narrative. The idea is that by using objects to tell a story, pupils get the chance to see many different artefacts.

A favourite story is the ancient Greek myth, Jason and the Argonauts. This includes, amongst other things, two kings, a beautiful island, a sorceress, and the magical mountains of Symplegades. You asked specifically how I used the Nicholson painting – this is ideal for the part of the story where Jason has to negotiate his way through the dangerous water passage that divides the two mountains. Nicholson's painting essentially is divided into two main areas of geometric shapes which are cut in two by a grey vertical stripe. These two areas, for the purpose of the story, represent the mountains whereas the stripe itself represents the waterway. A lot of artistic license is used by associating an abstract painting with two mountains and a water channel but this is ideal for introducing children to the concept of abstract art as well as getting them to use their imaginations.

So, the stories are fictional/mythological. The imaginative approach you identify doesn't preclude aspects of historical context and other analysis – for example as well as the Nicholson painting 'being' the Symplegades mountains, it is also identified as an abstract painting.

SH: It's fascinating to hear more about your use of narrative for interpretation.

I think using the Nicholson (1894–1982) painting as part of the Jason narrative works so well. I like how this combines visual analysis and the re-enactment of ancient myth – and that the latter encourages the former.

For me, the large grey forms in this image link with a fascination with ancient monuments on the part of British artists up to the Second World War [3]. When working on the Circle journal in 1937, Nicholson's then-wife the sculptor Barbara Hepworth (1903–75) accompanied her essay on modern sculpture with photos of ancient megaliths, and Nicholson’s work bears an interesting relationship with hers, in terms of use of form and space. He was also living in Cornwall at this time, an area with lots of these ancient sites. So, this work could allude to these symbols of ancient power too – and that works well with the Jason narrative: the cliffs controlled by the gods, in synergy with these ancient structures we think of as ritualistic.

Thinking more about narrative, the composition of the image also reminds me of a book, with the left and right forms like an open page spread, and the grey shading as the middle the centrefold. Following this idea, there's progression from one side to the other: from colour to monochrome, depth to shallowness, solidity to outline, and so I feel encouraged to read from left to right, as if the work presents a story or narrative of form.

Overall, there's so much that interests me about how you enact these images through narrative. I like that a series of images are drawn into one narrative – clearly encouraging audiences to make visual connections between different works. I fully take your point, that this doesn't preclude historical or other forms of analysis.

I've taught an MA course on Text and Image in which we analyse the different ways text in different forms (literature, novels, poems, reviews) can connect with images. Examples of these relationships include where a text describes an image, narrates and dramatises an image, tells a story based on but also moving away from the image, and/or tries to influence how a reader will view an image.

We look at examples of artworks where poetry has been written for artworks, to accompany them, or about them; novels where an artwork plays a part in the story; reviews where a critic tries to evoke their experience of looking at a work.

I wonder whether, beyond 'Stories in Art', you've considered seeing if you could do the same with your permanent collection as a temporary reinterpretation for the public? This might be a way to get people looking more closely and in different ways at the art, particularly art they may have seen many times, and a means to rejuvenate or refresh interest? I could see it working with the Modern British works, selecting appropriate texts (perhaps British ones to go with the art?) around a shared theme and then pairing them with certain works.

BS: I found the information relating to the British artists' fascination with ancient monuments very interesting, and yes that links in very nicely with the Nicholson/Jason narrative and the magical mountains!

I also like your connection of the Nicholson painting to a book. Funnily enough I was showing a group of Year Nine children the Nicholson painting yesterday and a pupil made a very similar link – she said it reminded her of an open book.

The text/image aspect you talk about is also interesting. I recently read Ali Smith's novel Autumn (2016), in which she includes references to the life and work of Pauline Boty (1938-66), and even includes an image of one of her paintings. This is an artist who I didn't know much about previously but who (as a result of reading the novel) I am now very familiar with. I am very interested in your idea of pairing texts with works of art!

SH: I love the link with British art and ancient objects in the 1930s and 1940s. There's a Sam Smiles article about this and he talks about Paul Nash (1889–1946) in this context too – I think you have one of his works in the collection? And the Ali Smith book sounds really interesting – I'll give it a read. I do like Boty's work, and find her practice and life really fascinating.

As a final thought for our conversation, I'm interested in what we can summarise about how our approaches to interpretation compare, from our respective positions in academic and arts education. So, I wonder, what do you feel interpretation of art in an education context seeks to achieve? What is it concerned with in general?

BS: As a Learning Officer I am responsible for different aspects of interpretation. As well as school workshops I also write family labels for exhibitions. These are usually written with the idea of getting family members to look closely at a work of art/object, therefore sharing/enjoying the experience together.

Making works of art/objects accessible is at the core of everything I do, and obviously this will vary depending on the audience. Yesterday I ran the Stories in Art workshop for a group of twenty-one EAL (English as an Additional Language) pupils. The teacher made the following comment on her evaluation: ‘My class were engrossed from start to finish – it was perfect for them. Very interactive.' As the pupils had limited English the emphasis was on the role-play and acting which worked to engage them as it was fun; as much as anything, I see my job as making the learning experience fun.

P.S. Yes, you're right – we do have a painting by Paul Nash (The Stackyard, c.1925) in the collection.

SH: I'm thinking about how I use interpretation in an academic context and I'd like to look at where our two approaches come together (or digress), and what they can learn from each other. I feel the point where we most closely overlap with our respective practices is in encouraging close looking. What I find fascinating about the approach that you use, given your aim is accessibility and enjoyment, is how you make things interactive.

From an art-historical perspective, close looking and analysis of artworks is at the core of our practice, but as it tends to have a particular academic function – to evidence an argument or historical enquiry – it sometimes falls subservient to these things. From our conversation, I've realised that I need to think of more captivating ways to bring close looking into my teaching – thinking beyond historical context to different ways to get students teasing out significant visual details – and looking at ways to be interactive would definitely work in this regard, to help students develop those close looking skills.

I too work with students with English as a second language, and it's helpful to see how creative close looking can work for this group of learners in particular, as a way to engage and enthuse them in their study. I'll certainly start thinking about how to enact this across my own practice.

From our last few emails, I've found myself thinking more reflectively and critically about my own methods for close looking and interpretation in my research practice and about the fascinating ways in which method can impact interpretation. For example, our conversation has led me to think differently about the effect of art writing that is more creative and imaginative. This has made me reconsider my research on how art writing and different spatial environments impact on viewing practices in historical contexts [4].

Do you have any thoughts, based on our conversation, on how our approaches compare? Is there anything from our conversation you’ve found particularly interesting/useful, that could inform your own work?

BS: Well yes, there have been some really useful pieces of information from our conversations that I have included in my sessions.

I now include the information about Nicholson's (and his contemporaries') fascination with ancient megaliths when discussing his painting with older students. For example, with Eardley, the link between the milk bottle and the female figure that you pointed out has been useful to further the argument that the figure is probably the boy's mother. As I have mentioned previously, the children in the gallery often associate the blue paint smudge on the face with a tear (i.e. the boy is crying). As you know, I was fascinated by your interpretation of this being possibly drawing attention to the artist ('showing her hand'), and wondered what you thought of taking this a step further. As the blue smudge is evidently at odds with the rest of the painting, could it actually be meant to be, as you say, the artist showing her hand, and be understood as Eardley's tear and not the boy's? It's just a theory (I may be being fanciful).

I must tell you a story about a workshop from last week. A group of Year Four pupils were sitting in front of the Thomas Lawrence painting and before I could get started on my presentation, a girl in the class interrupted me to tell me that she had seen this painting before. Furthermore, she told me that if you were to walk across the front of the painting the king's shoe (his right foot) would point at you wherever you stood in relation to the painting. I assumed that she may have been getting mixed up with another painting she had seen, but lo and behold, when we all tried it (which we all did) it really worked! As if the shoe moved as one walked by the picture. This is something that I hadn't come across before and will now use in my sessions, purely because it's fun! Also it goes to show that we can all learn from each other in our attempts to interpret works of art: Academics – Gallery Educators – Children – Gallery Educators – Academics (add to list/change order and carry on to infinity!)…

About Brian Scholes

About Brian Scholes

Brian Scholes, Learning Officer (Schools), The Herbert Art Gallery & Museum Coventry: I am a former secondary school art teacher, originally from Manchester. I have worked in galleries throughout the West Midlands for the last 19 years. I am passionate about teaching from objects and making learning accessible and fun!

About Sophie Hatchwell

About Sophie Hatchwell

Sophie Hatchwell, Lecturer, University of Birmingham: I am a historian of visual culture, and my research focuses on text-image relationships and the dissemination of art in Britain in the twentieth century. I'd welcome conversations and collaborations on text-image relationships in art and display, and on art interpretation in the public gallery.

Endnotes

Endnotes

[1] The object file for this work draws on scholarship that elaborates on issues of status and politics. See object file for Sir Thomas Lawrence, Portrait of King George III (1792), Herbert Art Gallery & Museum, VA.1950.23.1.

[2] A notable example is in the work of William Nicholson (1872-1949). See, for example, essays on The Conder Room (1910) in Morna O'Neill and Michael Hatt (eds), The Edwardian Sense: Art, Design, and Performance in Britain, 1901-1910 (New Haven and London, 2010), pp.117-89.

[3] See Sam Smiles ‘Equivalents for the Megaliths: Prehistory and English Culture, 1920–50’ in David Peters Corbett, Ysanne Holt and Fiona Russell (eds), The Geographies of Englishness: Landscape and the National Past 1880–1940 (London, 2002), pp.129–233.

[4] Here I refer to my research on Edwardian art writing, and particularly ekphrastic criticism by critics like D.S. MacColl, who in some articles, used a form of creative prose-poetry to critique contemporary art.