Andrew Tift’s Three Black Country Steelworkers (1992)

Object in Focus: Uncovering an Industrial Subculture

This article explores how Andrew Tift's Three Black Country Steelworkers (1992) works effectively as a social document, celebrating and commemorating a dying trade, but also alluding to darker social issues brought about by deindustrialisation and racial tensions.

Collection: The New Art Gallery, Walsall

Download a PDF of this article

Keywords: Andrew Tift, Portraiture, Race Relations, Deindustrialisation.

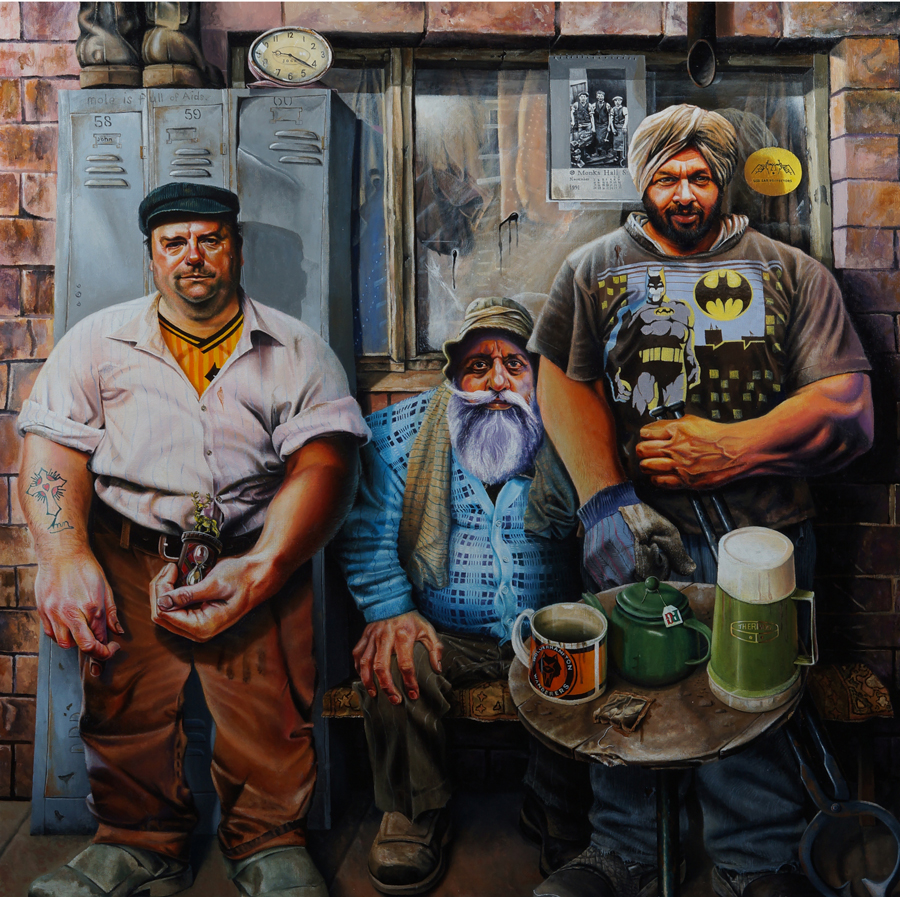

Fig.1 Andrew Tift,Three Black Country Steelworkers (1992), acrylic on canvas, 99 x 98 cm. Courtesy Andrew Tift; courtesy The New Art Gallery Walsall.

In Andrew Tift's Three Black Country Steelworkers (1992) (fig.1), three men look out at the viewer, appearing at ease. The men are on their tea break at Woodstone Rolling Mill in Wednesbury. Tift (born 1968) highlights the physicality of their work, as well as the changing racial demographics of the Black Country. One man holds a sand timer, suggesting that time is running out for the steelworkers as foundries were being closed due to the recession and government intervention [1]. The painting is, to an extent, an idyllic commemoration of the proud, hardworking foundry men. However, elements of the bleaker side of their trade are also evident: the brutality of steel foundry work, cultural tensions, and growing anxiety surrounding the deindustrialisation of the steel industry and job cuts. This article unpacks the complex imagery of this work, alongside the social and economic climate of the Black Country during the early 1990s. While Tift fulfils his aim to 'uncover and define an industrial subculture', the hardship that these steelworkers faced is only suggested subtly [2].

This painting was part of a major project that Tift completed for his Master of Arts at the University of Central England in 1992. The project was based on extensive research, and aimed to shed light on the remaining steel foundries in the Black Country. Tift spent a lot of time in the foundries, speaking to steelworkers and getting to know their environment. What he discovered is depicted in the sketches, paintings and collages he made. Tift intended these works to form what he calls 'an industrial archive' or 'social study' [3]. One could also call this work a memorial to a dying trade. Three Black Country Steelworkers is an interesting case-study. While other works in Tift's project focus on the fragility of architectural structures, this painting centres on the similarly unstable positions of the people who worked within these structures. It can be considered the artist's first major portrait and as such a milestone in his career. Tift has subsequently worked primarily with portraiture and has achieved prestigious accolades for his work, including the National Portrait Gallery's BP Portrait Award in 2006.

While his recent portraits are realistic, during the early 1990s Tift's style was more expressive. The artist comments that one should not call his work distorted, to avoid suggesting that the information he collected has been misinterpreted. He argues that one should refer to the work as a 'translation' or 'interpretation' of his research [4]. While it is designed to document, each element uncovering something about the steelworkers, the painting is undoubtedly complex and ambiguous. This is also intentional, the artist 'presenting the viewer with a thought-provoking visual puzzle to solve' [5]. As well as being documents, these are also images invested in the history of art. Tift has discussed the influence of Old Masters on his painterly style and Hans Holbein the Younger's The Ambassadors (1533) is strongly reflected in this work – although the status of the sitters is very different [6]. These allusions to The Ambassadors are perhaps a method of dignifying the sitters, situating them within the history of art and portraying them in a manner previously used to represent the nobility. The various objects crammed into the sixteenth-century painting, which reveal elements of sitters' biographies, are echoed in Tift's crowded composition. For example, a mug and one man's t-shirt display the orange and black Wolverhampton Wanderers FC logo. A calendar hangs behind them depicting three nineteenth-century steelworkers, commenting on the well-established history of their trade. Much like The Ambassadors, the steelworkers are painted as they wish to be remembered, the fragility of their positions only hinted at.

Arguably, the work is designed to be understood by a specific audience – those living in the Black Country during the 1990s, who were affected by, or at least aware of, the deindustrialisation of the steel industry. These viewers may recall their own experiences of hardship and struggle, whereas to a wider audience, this work could be more generally an image of pride and comradeship. While the painting depicts carefully studied individuals, the figures are, to an extent, anonymous. Only the title of the painting groups them together, and their names are left unknown. Tift is a local artist, born and raised in the Black Country. He donated the work to The New Art Gallery Walsall, and it was never intended to be for commercial sale. One gets a sense that the artist believes in art's ability to affect local communities positively, demonstrated for example when he spoke out in 2016 against Walsall Council's proposal to reduce funding for The New Art Gallery, which might have led to its closure. He argued that the opening of the gallery was 'the best thing that ever happened to Walsall' and 'without it the town would be nothing' [7]. This deep interest in his local community is echoed in the portrait.

In one sense, the tone of the work is positive, emphasising the physical strength and pride of the steelworkers. This is evident in the figures' bulging hands, feet and muscles, strongly defined by dark shadows. The composition is cramped, the over-sized workers filling most of the canvas. Tift was perhaps influenced by Stanley Spencer's Shipbuilders on the Clyde (early 1940s), eight paintings depicting the processes involved in making merchant ships. The series was based on the town, Port Glasgow, which Spencer visited as an official war artist during the Second World War [8]. Spencer's shipbuilders are painted in a similarly expressive manner to Tift's steelworkers. Mike McKiernan comments that Spencer conveys working life idyllically, showing 'no conflict, grease or sweat' [9]. Tift's work has a similar tone, not even depicting the men at work, but relaxing during their tea break. Labour is only inferred through the oil stain on the trouser-leg of John Isley, the figure on the left with rolled up sleeves.

However, unlike Spencer's shipbuilders, Tift's steel workers are not entirely harmonious. The painting comments on the growing racial diversity in the Black Country. The two men on the right, Bant Singh and Kundan Singh, are Sikhs. During the dramatic rise in demand for labour in the early 1950s in Britain, many men arrived from the Punjab in hope of finding work. Shortages were particularly extensive in manufacture, and many new arrivals secured jobs in steel foundries [10]. Billy Dosanjh's documentary The Sikhs of Smethwick (2016) focuses on the experiences of different generations of Sikh families living in the West Midlands town. It explores concerns around the lack of integration and hostilities that the first Sikhs arriving in Smethwick faced. A first-generation migrant to the Black Country comments that, 'when I came to England I was overjoyed, I didn't know how hard life would be' [11]. Men arriving from the Punjab in the early 1960s inhabited 'cheap inner-city slum dwellings, often scheduled for demolition or clearance' [12]. Dosanjh says that many first-generation British Sikhs never learnt English, living in an isolated Punjabi bubble. This was often because they did not have time to learn, working around the clock to support their families [13]. Over time men saved money to bring their families to Britain, buy houses and become more established members of the community [14]. However by 1992, conditions had deteriorated once more for Sikhs in the Black Country. Terrible consequences were faced by many, due to the industrial recession and subsequent job cuts, particularly those first-generation Sikh workers who were not able to write or read English. A 1996 Birmingham City Council report stated that, due to a lack of support from local government and financial institutions, 'many Sikh families are faring badly' [15]. The struggle they had experienced almost 25 years previously were echoed during this recurring period of hardship.

The painting also alludes to the new social and cultural interactions and tensions that emerged in the Black Country. Kundan (worker furthest to the right) wears a turban, a significant marker of his Sikh identity. In the Black Country workplace, the turban could invoke a particular history of protest and racial tension. Following a ban on Wolverhampton bus drivers wearing turbans, a two-year dispute ensued surrounding Sikh customs at work. Kassimeris and Jackson's analysis of letters to the local press at this time shows the ways in which the protest about Sikh dress unravelled into a dispute over migration and integration. Indeed, it was partly in response to the local Sikh protests that the Wolverhampton MP Enoch Powell delivered his infamous, divisive 'Rivers of Blood' speech in Birmingham in 1968 [16]. Similar issues occurred in the 1970s and 1980s, however all were resolved with workers allowed to wear their turbans [17]. In the painting Kundan stands tall, proudly donning this symbol of his identity. He also wears a Batman t-shirt, and Tift paints him mimicking the character's stance, perhaps suggesting that he admires the masculine ideal that this superhero represents. Viewers might make connections between Kundan's t-shirt and the steelworkers' emphasis on masculine strength, which was particularly strong among some Sikh men. According to Billy Dosanjh this had implications in their work environment, men often competing over the heaviest job [18]. However, Tift's conversation with Kundan reveals that he did not know anything about Batman, and had bought the t-shirt to work in because it was cheap. Tift calls this a 'wonderful culture contrast'. I think it operates as a comment on the assumptions and connections that viewers might make between masculinity, American superheroes, and cultural integration [19].

Although the three workers stand together, they do so somewhat awkwardly, appearing simultaneously as a group but also as separate figures. Segregation was reported in factories, and in one Midlands factory, complaints about Sikh habits were so frequent that they were built a separate toilet. Robert Winder comments that, ironically, it was much better looked after than the English ones [20]. This is reflected somewhat in the steel foundries as, following his research, Tift said that 'there has been a cultural segregation which has never been bridged' [21]. At Woodstone, workers built cabins in which they spent their breaks; the three men in Tift's painting stand outside their cabin. These spaces were personalised, the artist commenting that they 'reinforced a very human side to the harsh Dickensian-style environment'. However, they were also used to mark territory and social groups, and at Woodstone, Asian and white workers were often divided. The cabins were 'exclusion zones' which people were only allowed into if invited by another member of the group [22].

Arguably, the exaggerated forms in all three figures convey hyper-masculinity, compensating for, or attempting to disguise, the vulnerability and powerlessness that the workers felt as foundries closed and jobs were cut. Tift visited three foundries during his project, one of which shut down in the course of his research period [23]. The building in which the painting is set is the only remaining one of thirty-nine which once made up Woodstone Rolling Mill [24]. The artist comments that his goal was not to celebrate their working methods, but to focus on their plight [25]. He depicts men who stand strong in the face of hardship, however weakness and fear peep through cracks in this veneer.

According to Dosanjh, working conditions in the steel foundries were brutal and unsafe [26]. Generally, men did not wear uniform and often suffered injuries from hot metal [27]. Sikh men were particularly in danger, often taking jobs that English workers would not accept due to extremely hard conditions, low pay and irregular hours [28]. In Tift's work this is alluded to as the men wear their own clothes and although they wear steel toe cap boots, neither goggles nor safety helmets are worn to protect them from the hot metal. Kundan grasps his furnace tool, perhaps with a sense of pride and fulfilment from his profession. However, his tight grip, with veins bursting from his hands, also suggests that this depiction of happy workers disguises a harsher reality.

Tift focuses on imagery of time and history. Time is running out for the steelworkers, evident as John clasps a sand timer protectively, and a clock sits over the edge of an old battered locker, as if about to topple off. The calendar which hangs behind the steelworkers creates a sense of wistfulness and nostalgia – this well-established, once thriving trade is now dying out. John crosses his fingers for good luck, the strain in his muscles suggesting his concern about their uncertain future. The lockers are rusting and battered, worn boots resting above them, the window smeared with dirt. The table in the foreground tips towards the viewer and it appears that the drinks may clatter to the floor at any moment. Everything lurches on the brink of collapse. Billy Dosanjh explains that growing unemployment led many Sikh men to alcoholism, their ethos of manliness and strength defeated [29]. Although these catastrophic consequences are not explicitly portrayed in the painting, it gives a sense of the future struggles of these workers.

In Tift's exhibition Immortalise, on display at The New Art Gallery 25 May-2 September 2018, it is startlingly clear that, although his style has developed, the artist's goal remains the same even 26 years later; to immortalise his sitters in paint. The artist commented that the closing of foundries 'heightens … the urgency and necessity to document these dying industries before they disappear altogether' [30]. In Three Black Country Steelworkers, Tift uses objects and symbols to reinforce the sitters' identities. Richard Brilliant's statement that 'a portrait is a sort of general history of the life of the person it represents', is certainly applicable to this painting [31]. The portrait serves to give marginalised people dignity as well as to record their place in history. This complex painting succeeds in uncovering an industrial subculture, both celebrating the steelworkers' trade and common working culture, and alluding to the darker social issues brought about by racial tensions and deindustrialisation.

About Mimi Buchanan

About Mimi Buchanan

Mimi Buchanan is an MA Art History and Curating student in the Department of Art History, Curating and Visual Studies at the University of Birmingham.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements

My thanks to Andrew Tift for sharing his Master of Arts dissertation with me. Also, thanks to Julie Brown, Curator at the New Art Gallery Walsall, who provided access to material relating to Tift's work.

Endnotes

Endnotes

[1] Race Relations Unit: Birmingham City Council, The Sikhs in Birmingham: A Community Profile (Birmingham, 1996), p.15.

[2] Andrew Tift, 'A Socio-Cultural Study of the Effects of De-Industrialisation of the West Midlands Steel Industry Using Figurative Painting to Document the Change', unpublished MA dissertation, University of Central England (1992).

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Unknown Author, 'Why closing Walsall's New Art Gallery would leave the town with nothing', Express & Star (10 November 2016), accessed 20 June 2018.

[8] Fiona MacCarthy, Stanley Spencer: An English Vision (New Haven and London, 1997), p.42.

[9] Mike McKiernan,'Shipbuilding on the Clyde: Burners 1940', Occupational Medicine, 64.7 (2014), p.482.

[10] Gurharpal Singh and Darshal Singh Tatla, Sikhs in Britain: The Making of a Community (London, 2006), p.50.

[11] Billy Dosanjh, The Sikhs of Smethwick, BBC Documentary, broadcast on BBC Four (2 December 2016), accessed 10 September 2017.

[12] Singh and Singh Tatla (2006), p.53.

[13] Dosanjh (2016).

[14] Ibid.

[15] Race Relations Unit (1996), p.58.

[16] George Kassimeris and Leonie Jackson ‘Negotiating Race and Religion in the West Midlands: Narratives of Inclusion and Exclusion during the 1967–69 Wolverhampton Bus Workers’ Turban Dispute’, Contemporary British History, 31.3 (2017), pp.343–65.

[17] David Feldman,'Why the English like Turbans: Multicultural Politics in British History', in David Feldman and Jon Lawrence (eds), Structures and Transformations in Modern British History (Cambridge, 2011), pp.281-2.

[18] Dosanjh (2016).

[19] Tift (1992).

[20] Robert Winder, Bloody Foreigners: The Story of Immigration to Britain (London, 2010), p.356.

[21] Tift (1992), p.65.

[22] Ibid., p.17.

[23] Ibid., p.89.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Dosanjh (2016).

[27]Ibid.

[28] Singh and Singh Tatla (2006), p.148.

[29] Dosanjh (2016).

[30] Tift (1992).

[31] Richard Brilliant, Portraiture (London, 1991), p.37.