Realism and the Multiple: Pietro Magni’s Reading Girl (c.1861)

This short essay reflects my research interests in the representation of children and adolescents in sculpture, public statuary, and on sculpture’s relationship to the contemporary world. In particular it focuses on Italian nineteenth-century realism in sculpture, reproduction and exhibition histories.

Keywords: sculpture, Italy, 19th century, realism, reproduction, histories of exhibitions

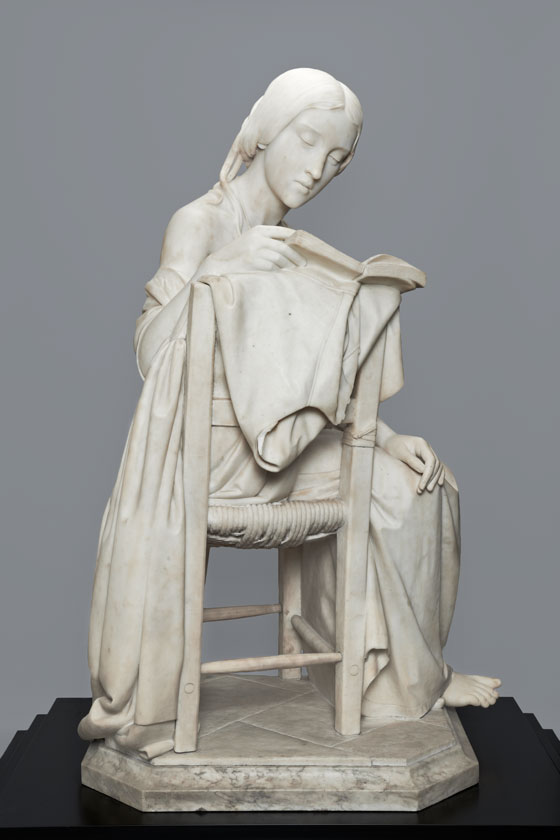

Fig.1 Pietro Magni, The Reading Girl (c.1861), marble, 91.44 cm ©Research and Cultural Collections, University of Birmingham

Located in the Cadbury Research Library is a marble statue of a girl reading, which dates from around 1861, and was created by the Italian sculptor Pietro Magni (1817-77). This sculpture might seem unremarkable, yet it represents a complex shift in sculpture, from the timeless qualities of ideal classicism towards a new engagement with the contemporary world. In this short essay I will reflect in particular on the work’s exceptional realism, questions of reproduction, and exhibition histories. There are various known versions of this statue. Surprisingly, the version at the University of Birmingham appears to have been previously unknown to scholars. It is not referred to in the scholarship or in the extensive catalogue entry for the version now at the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC [1]. This is indicative perhaps of the status and visibility of university collections in comparison to more ‘standard’ museum collections (including within their own institutions), and the secondary importance placed on reproductions or variations in art history.

The Reading Girl is a marble sculpture of a girl reading. She sits on a rush-bottomed chair, side-on, intently reading a book which is supported on the top rail of the chair back. Her bare feet rest on a flagstone floor. This is not a wealthy or ideal setting, but a relatively poor interior scene. This is reinforced by the condition of the chair, which appears to have been broken; there is a tie around one of the uprights, suggestive of a split or break. The girl is dressed in a chemise with short sleeves, with visible stitching, hems, gathers and folds. Her outer dress, with its stitched bodice and button hoops, hangs on the back of the chair. Her hair is brushed smooth and parted, and gathered at the back in a large plaited roll, secured with a decorated hair comb. This neatness is disrupted by tendrils of hair on her brow, and unruly locks that sweep down her right shoulder. This mirrors the curve of her chemise, which has slipped down, exposing her narrow back and projecting bones. Her right breast is left fully exposed, while further undress is prevented by the chemise’s stitched placket, which tugs at her waist. Around her neck is a string bearing a portrait medallion (fig.2).

Fig.2 Pietro Magni, The Reading Girl (c.1861), marble, 91.44 cm ©Research and Cultural Collections, University of Birmingham

The impression given is of a reader so enthralled, that they are unaware of their uncomfortable reading position, cold floor, or exposed body. She is unselfconscious, and in this particular portrayal of a pubescent girl, this lack of shame carries with it the association of innocence. Yet her absorption also isolates her as an object to be approached, examined, and even touched. I am interested more broadly in how children are represented in sculpture, and a forthcoming essay addresses the erotic dimensions of the combination of realism, cloth and puberty in mid-nineteenth century Italian sculpture [2]. For this essay, I focus on questions of realism.

As a category within the history of sculpture, the Reading Girl is an example of mid-nineteenth century Italian verismo sculpture. This stunned and enthralled British viewers when they first became acquainted with it through the international exhibitions that facilitated the global movement of artworks across the century, beginning with the Great Exhibition in London in 1851. The Reading Girl was one of the star turns of the London International Exhibition of 1862. What drew the crowds and critics was its realism, which was unprecedented in British sculpture at the time. Next time you visit the Cadbury Research Library, look closely, and you will see how the sculptor has carved minute marks into the marble, imitating stitches, folds and creases in cloth; how the base of the sculpture has been carved and finished to imitate a flagstone floor; the tear that has fallen to her cheek; the dry texture of the plaited cord around her neck; the woodiness of the chair with its pegged construction; the leaves in the book; and the cuticles around her nails.

The detailed rendering of material objects and living bodies typifies the new sculptural realism emerging from northern Italy in the 1850s and 1860s. British art critics applauded this technical virtuosity but also dismissed it as a superficial engagement with detail and surface. Subsequent historians have similarly drawn attention to the realism of these works [3]. I have argued, however, that, in stark contrast to the later realism of the New Sculpture that emerged in Britain in the 1870s onwards, the surface detail of this earlier Italian sculpture has been confined to discussions of technical virtuosity. I suggest instead, that the surface detail in works such as the Reading Girl is far from superficial, and offers radical – and sometimes unsettling – new ways of engaging with the modern world.

Indeed, as the art historian and critic Joseph Beavington Atkinson (1822–1886) noted in 1862, this realism refers to the way it represents both real objects and real (rather than ideal) people:

Magni's ‘Reading Girl’, truthful not only to the hem of a garment, to the turned leaf of the book, and the torn rushes from the bottom of cottage chair, but earnest as if the whole soul drank of the poetry and was filled, moves with a heartfelt pathos ... The girl reads, and among the crowd of spectators every voice is hushed. Tread softly, break not rudely on her reverie. Listen! perchance she speaks [4].

The novel depiction of such every day subjects as a peasant girl reading and the particularity of her rush-bottomed cottage chair, offered a new departure in sculpture, which differed from and challenged the centrality of the ‘ideal’ classical Venus in sculpture. Interestingly, Atkinson remarks on the novelty of this sculpture, but also roots it within a longer, and classical, history of sculpture, drawing connections between the Reading Girl and the classical sculpture of the Dying Gaul as rare examples of working class and enslaved people depicted in sculpture. This connection between nineteenth century sculpture, classical sculpture and the contemporary every day is central to my current book project on sculpture in nineteenth-century Britain.

In the case of the Reading Girl, the realism of its surface and subject matter encouraged visitors to engage with it in a way that was increasingly being discouraged, at least in museums. As one critic observed, when it was displayed at the International Exhibition in Dublin in 1865, the public felt able to touch it:

The tendency of modern popular sculpture is to be material and realistic … Tens of thousands [of the hundreds of thousands who saw the ReadingGirl] enjoyed the luxury of putting their hands on the wicker-work of the chair, and were thrown into rhapsodies [5].

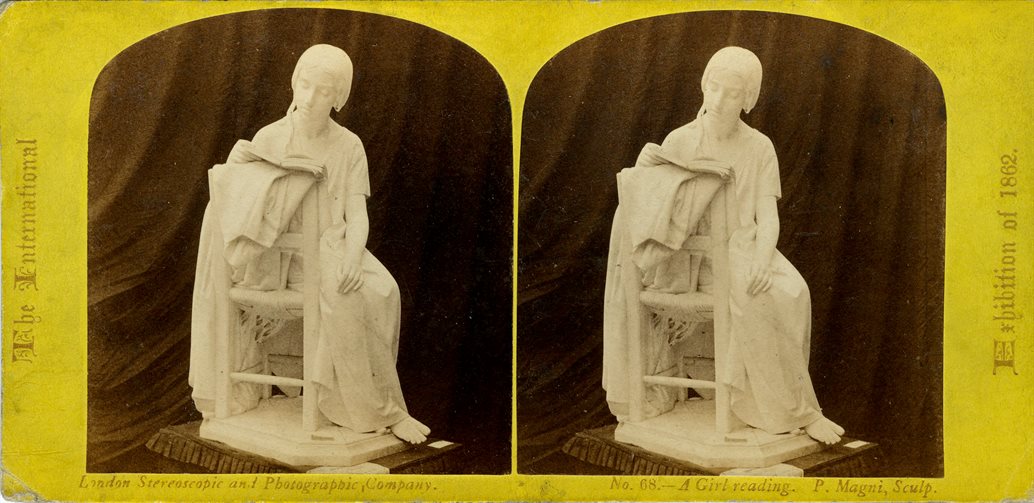

This passage suggests a very public, performative and collective interaction with sculpture, within the specific context of the international exhibitions. While the chair might not seem to be the most distinctive feature of the Reading Girl when viewed at the Cadbury Research Library, the reference to ‘torn rushes from the bottom of cottage chair’ in Atkinson’s earlier quotation is significant. There were different versions of the Reading Girl in circulation. The ‘torn rushes’ refer to the complex carving of protruding rushes carved in the underside of the chair, visible on contemporary stereograph cards and engravings of the work (fig.3), and visible on the Reading Girl now at the National Gallery of Art in Washington [6].

Fig.3 London Stereoscope and Photographic Company, International Exhibition of 1862: The Reading Girl, P. Magni (1862), stereograph card. Author’s collection

The torn rushes are not reproduced in the version at Birmingham. The latter is nevertheless still spectacularly realist in its carving, with even the underside of the rush seat fully carved, and the pegged joints to the chair clearly delineated. This reveals how Magni was intent on sustaining the illusion of its ‘chairness’ through sustained detailed carving throughout the piece. The underside of the chair would perhaps have been more visible when the work was displayed at the international exhibitions, than the low plinth it currently rests on. We are meant to be drawn in, to peer, to examine in detail, explore underneath as well as around the work, and marvel at the skill of this sculptor; and to succumb to the illusion.

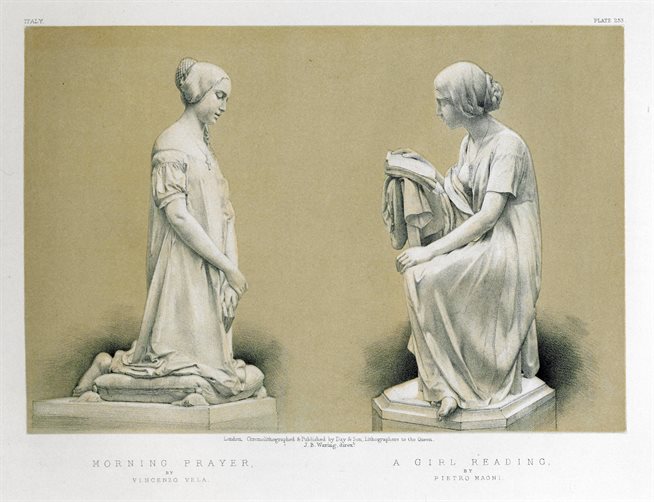

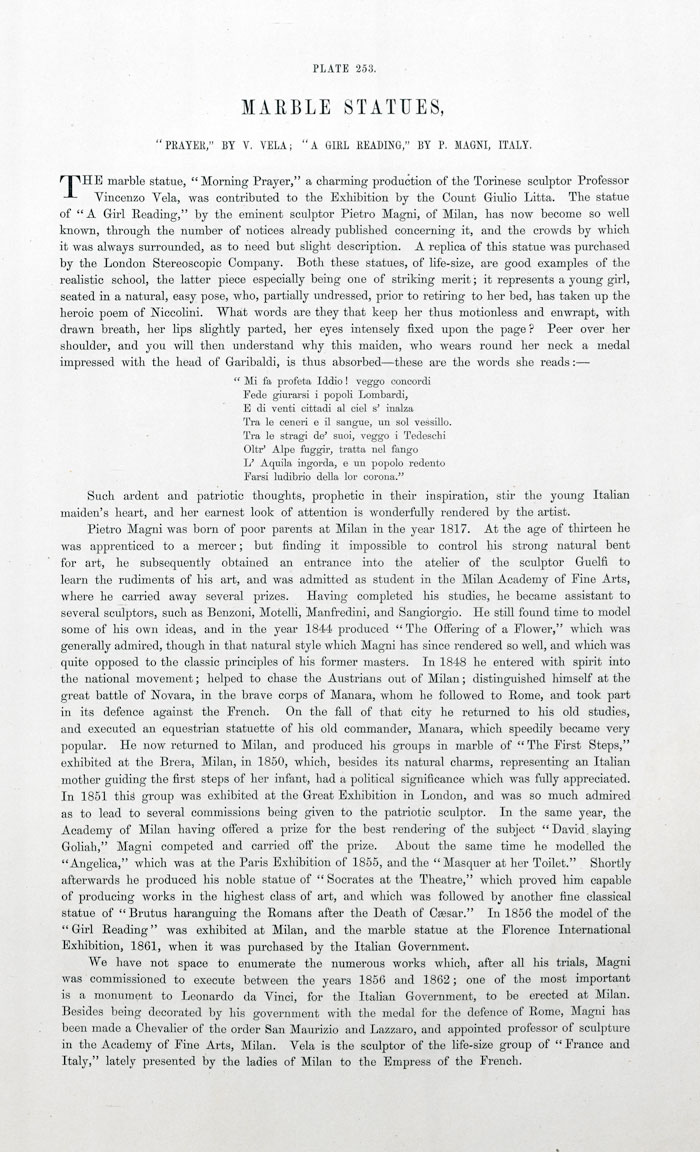

It makes sense that the Italian Ministry of Public Information sent the most complex version of this work, with its protruding underbelly, to the International Exhibition of 1862. The purpose of these exhibitions was to compete with foreign nations in producing and showcasing the most advanced examples of technical and artistic skill. The strategy worked. The architect and curator John Burley Waring included it in his ambitious three-volume illustrated Masterpieces of Industrial Art and Sculpture at the International Exhibition, 1862, and noted in the accompanying text that it had ‘become so well known, through the number of notices already published concerning it, and the crowds by which it is always surrounded, as to need but light description’ [7]. Below are reproductions of Plate 253, a chromo-lithograph of the Reading Girl (fig.4), and its accompanying text (fig.5), from Waring’s Masterpieces.

Fig.4 J. B. Waring, A Girl Reading by P. Magni, chromo-lithograph (1863) J. B. Waring, Masterpieces of Industrial Art and Sculpture at the International Exhibition, 1862 (London, 1863), vol.3, plate 253 ©Cadbury Research Library, University of Birmingham

Fig.5 Text accompanying fig.5. J. B. Waring, Masterpieces of Industrial Art and Sculpture at the International Exhibition, 1862 (London, 1863), vol.3, plate 253 ©Cadbury Research Library, University of Birmingham

As you read through Waring’s description, you will have noticed that he interprets the Reading Girl as a political sculpture. As mentioned previously, she wears a portrait medallion of the Italian general, politician, nationalist and anti-Catholic Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807-1882). His religious views were particularly pertinent in Britain around the time of the International Exhibition of 1862, as there were fears from the Protestant majority about the resurgence of the Roman Catholic Church in Britain. Garibaldi’s efforts to overthrow the Pope galvanised public opinion, and led to the so-called Garibaldi riots of 1862 in Wakefield, Bradford, Leeds, Tralee in Ireland, London and Birkenhead [8]. At the International Exhibition of 1862, the Reading Girl read from an actual text, pasted to the marble book. These lines, transcribed by Waring, were taken from the Italian poet and playwright Giovanni Battista Niccolini (1782-1861), whose earlier writings celebrated themes of emancipation from the Austrian empire.

Waring connects the girl’s concentrated reading with patriotism; ‘Such ardent and patriotic thoughts, prophetic in their inspiration, stir the young Italian maiden’s heart, and her earnest look of attention is wonderfully rendered by the artist’ [9]. Subsequent scholars and curators have similarly focused on the work’s political content. As Nicholas Penny observed in a 2008 essay on the Reading Girl, her youth can be directly associated with the nascent Italy; ‘the girl herself was understood to stand for the earnest young adolescent nation’ [10]. The Reading Girl might therefore represent the possibilities of growth and maturity in this new Italy. Yet, as previously mentioned, there were different versions of this sculpture. And one of those wears a crucifix.

The Reading Girl is and is not a single object. There are different iterations of this statue, each of which share the same name [11]. The scholarship has differentiated between these different sculptures by distinguishing between those that bear a medallion of Garibaldi (like the version in the Cadbury Research Library), and those that bear a crucifix. It has yet to think across the political and religious meanings of these works, or to consider how they might operate side by side. Research has focused on the former, perhaps because the formation of modern nation states is easier to position within a history of modernity, than the sustained presence of religion during a century of radical change. This will hopefully shift, as studies, including my own forthcoming book on sculpture in nineteenth-century Britain, revisit nineteenth-century documents to consider what was significant to contemporaries, irrespective of what might have been selectively highlighted by subsequent historians. Art history as a discipline has also tended to give precedence to the ‘original’ work, and rarely considers the copy itself in detail, or questions of variation and the creative potential of reproduction [12]. The Reading Girl is an example of a work that was explicitly modified for different political and religious patrons and audiences, and further research might advance our understanding of the role of sculpture in these apparently separate spheres. It might also seek to consider these together, within a broader context of nineteenth-century Italy, and related themes of democracy, hegemony, division, unification, education, tradition and change.

The Reading Girl is also well travelled. She was displayed at the National Exhibition, Florence (1861), the International Exhibitions of London (1862) and Dublin (1865), and possibly also at Paris (1867), Vienna (1873), Chile (1875) and Philadelphia (1876) [13]. Versions are to be found in Birmingham and Washington DC as well as in Italy. These exhibition and collection histories further disrupt the idea of viewing the Reading Girl as a single work, because it opens up very specific histories of patronage, exhibitions, collections and display, to the study of each of these works. This offers a particularly rich seam for future research, given the political, national, cultural and economic factors at play in the national and international exhibitions that dominated the movement and reception of artworks in the nineteenth century. Research has so far centred on Italian sources and English-language receptions of the sculpture in London and Dublin; extending this to its reception in the international press, as well as its exhibition in Paris, Vienna, Chile and Philadelphia, would present an innovative study into the international movement and reception(s) of artwork(s), and their location within particular local, national and international narratives. The version at the Cadbury Research Library entered the University of Birmingham’s collections in the 1930s. Even if its provenance is not fully traced, and its various historical and display contexts remain unknown, we can actively consider its current role and function within a university collection, and find ways of enabling it to resonate with today’s visitors and researchers, raising questions, provoking thoughts, and perhaps even reading poems.

About Claire Jones

About Claire Jones

Claire Jones is Lecturer in the History of Art at the University of Birmingham. She would welcome conversations and collaborations on ideas of mobility, translation, reproduction, reception, realism, childhood, and nationalism.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements

With thanks to Martin Killeen, Senior Librarian, Cadbury Research Library, for sourcing Waring’s Masterpieces, and to colleagues at the Research and Cultural Collections for involving me in the exhibition ‘Curating the Campus: Highlights of the Research and Cultural Collections’, 19 September 2016 to 20 January 2017, The Bramall, University of Birmingham, in which the Reading Girl featured.

Endnotes

Endnotes

[1] On The Reading Girl, see Francesco Tedeschi, ‘La Leggitrice di Pietro Magni Vicende e problemi storico-critici’, OttoNovecento, 1 (1998), pp.5–12; Nicholas Penny, ‘Pietro Magni, The Reading Girl (La Leggitrice)’, National Gallery of Art Bulletin, 30 (2003), pp.14–15; Nicholas Penny, ‘Pietro Magni and his Reading Girl’, in C. Chevillot and L. de Margerie (eds), La Sculpture au XIXe siècle: Mélanges pour Anne Pingeot (Paris, 2008), pp.158–64; Sotheby’s London, ‘Lot 148’, European Sculpture and Works of Art 900-1900, auction catalogue (5 July 2000), pp.110–2; Stefano Grandesco, ‘La leggitrice’, in Maria Vittoria Marini Clarelli, Fernando Mazzocca, and Carlo Sisi (eds), Ottocento. Da Canova al Quarto Stato, exhibition catalogue (Rome, 2008), p.74.

[2] Claire Jones, ‘‘‘A Perverted Taste”: Italian depictions of Cloth and Puberty in mid-nineteenth century Marble’, in Alice Kettle and Leslie Millar (eds), The Erotic Cloth: Seduction and Fetishism in Textiles(London, forthcoming 2018).

[3] See note 1 above; Julius Bryant, ‘Bergonzoli’s Amori degli Angeli: The Victorian Taste for Contemporary Latin sculpture’, Apollo (September 2002), pp.16–21.

[4] J. Beavington Atkinson, ‘International Exhibition, 1862. No.VI – Sculpture, Foreign Schools’, Art Journal (November 1862), p.214.

[5] ‘Sculpture: the Dublin Exhibition of 1865’, Temple Bar (15 August 1865), p.56.

[6] For an engraving, see ‘The Reading Girl’, Art Journal (February 1864), p.57. The Washington DC version has a medallion of Garibaldi, and was acquired by the National Gallery of Art in 2003. See the National Gallery of Art’s online collection entry for this work, https://www.nga.gov/Collection/art-object-page.127589.html, accessed 9 September 2017.

[7] John Burley Waring, Masterpieces of Industrial Art and Sculpture at the International Exhibition (London, 1863), vol.3, text accompanying plate 253.

[8] Sheridan Gilley, ‘The Garibaldi Riots of 1862’, Historical Journal, 16.4 (1973), pp.697–732.

[9] Waring (1863), text accompanying plate 253.

[10] Penny (2008) p.164.

[11] The following summary of the different versions of the Reading Girl draws in particular on Tedeschi (1998), Sotheby’s (2000) and Penny (2008).

1856 First exhibited as a plaster at the annual exhibition at the Brera in Milan, no.344, La Lettura

1861 Marble version first shown at the National Exhibition in Florence. Acquired by the

Ministero dela Pubblica Istruzione (or is a new copy commissioned?), and transferred

to the Torino.

1862 Marble version owned by the Ministero di Istruzione Pubblica is exhibited at the International Exhibition in London.

Tedeschi suggests that Magni sent two copies to the International Exhibition (p.11, note 8). Presumably the second one is the one acquired by the Stereoscopic Company of London.

A version is purchased by the London Stereoscopic Company in 1862. The LSC also purchased Raffaelle Monti’s The Sleep of Sorrow and the Dream of Joy (1861, now at the V&A) in 1862, and both works were displayed in the LSC’s London showrooms in Recent Street and the City. Both works are reproduced as a series of stereographs, taking from different angles. At some point, by c.1900, both works were acquired by Mrs Croft, probably for the Winter Garden at Farnham’s Hall, Ware. This was sold for £5 in 1950 at the sale of the contents of Fanham’s Hall (Sotheby’s, 5 October 1950, lot 1001) but never claimed. It was then sold at Sotheby’s London (5 July 2000, lot 148). This version was then acquired by the National Gallery of Art in Washington, 6 June 2003. (Penny, 2008, p.161, notes 5 & 9).

1864 Three versions are known to have been carved by this point; two for patrons in London (one being the Stereoscopic Company of London – and the other unknown), and the earlier version made for the Ministero di Istruzione Pubblica.

1865 A marble version with a medallion of Garibaldi is exhibited at the International Exhibition in Dublin. This one has protruding rush work, and is presumably the one now in Washington (or Padua?).

Other versions

- An unsigned and undated version with a (now broken) cross around its neck was deposited at the Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan, in 1902, and now in the Museo d’Arte Moderna, Milan. It is dated to circa 1864, see http://www.gam-milano.com/en/collections/exhibition-itinerary/, Room XVI.

- A version with a Garibaldi medallion is held in the Museo Bottacin, Padua, see http://padovacultura.padovanet.it/it/musei/museo-bottacin-. According to Tedeschi, this version still holds traces of the printed pages that were attached to the marble. The underside of the chair also has protruding rush work, as remarked upon by visitors in Dublin in 1865, and it has a ribbon around the ‘break’ as at the Cadbury Research Library.

- A version wearing a medallion of Garibaldi, has been in the University of Birmingham’s libraries since the 1930s. It forms part of Research and Cultural Collections, University of Birmingham, and is located in the Reading Room of the Cadbury Research Library. Inscription on the paving near the sitter's foot: P Magni / Milano. Undated. Catalogued as 1861. This work appears to have been previously unknown to scholars; it is not referred to in any of the previous scholarship. For the online collections record, see http://mimsy.bham.ac.uk/detail.php?t=objects&type=all&f=&s=magni&record=2

[12] I have attempted to address the question of creative reproduction in a previous article, Claire Jones, ‘A Creative Engagement with Historic and Modern Sculpture: Waldo Story's Fallen Angel’, Sculpture Journal, 23.2 (2014), pp.145–58.

[13] On the Reading Girl at these exhibitions, see notes 1, 4, 5 and 7. See also: ‘The Art-Show at the Great Exhibition’, Dublin University Magazine (August 1862), p.141; ‘The Dublin International Exhibition’, London Reader (8 July 1865), p.296; Britt Salvesen, ‘“The Most Magnificent, Useful, and Interesting Souvenir”: Representations of the International Exhibition of 1862’, Visual Resources, 13.1 (1997), pp.1–32.