Memory on The Move in Eugene Palmer’s Wanting to Say I (c.1997)

In Wanting To Say I, Eugene Palmer (b.1955) painted a black woman – inspired by a photograph from 1930s America – who looks out at us from what appears to be the hull of a ship. This is a painting about movement (of slavery and migration) and finding a sense of selfhood and history across time.

Keywords: Eugene Palmer, migration, black history, memory

Fig.1 Eugene Palmer, Wanting to Say I (1997), oil on canvas over board, 84 x 82 cm ©Eugene Palmer ©The New Art Gallery Walsall

In Eugene Palmer’s Wanting To Say I (fig.1), a woman meets our gaze. She is a black woman rendered in tones of black and white, and we see just her head, a portion of her neck, and a small section of her shoulder. Her hair is swept over her forehead and around her ears. She wears a pince-nez, a pair of glasses without arms, with a chain running off one side, and which appears to be attached to her ear or perhaps clipped into her hair – these were particularly popular in the nineteenth century. Her head is closely cropped by a circular, cream border, so that her image takes the form of a tondo, a circular art work originating in Renaissance Florence. This tondo form is set within a larger rectangular canvas that has been painted to resemble steel: it is a rusty brown colour, covered in a series of discs that protrude slightly from the surface of the canvas and which take on the resemblance of rivets or bolts. Each one has been painted with a lick of dark brown paint, giving them a particular emphasis, underlining their solid presence. The result is that this woman appears to look at out at us at a slight remove, perhaps through a hatch or a window. It is tempting to read this as a port hole in the hull of a ship, with the woman looking out at us as she embarks on a journey. The ship has, of course, powerful resonances for black people, evoking histories of slavery and of migration, of journeys undertaken by force and by choice.

There are other, intersecting histories built into this painting too. The portrait of the woman is painted from a photograph taken by Richard Samuel Roberts, a black photographer born in 1880 who worked initially in Florida, and then in Columbia, South Carolina in the 1920s and 1930s, until his death in 1936. Roberts worked for the US Postal Service and taught himself photography in his spare time, before setting up his own studio. In Columbia, he worked in the post office from 4am until 12 noon, before walking to his studio in the city’s ‘Little Harlem’ to work with his photography clients there. He was one of only a very small number of African American photographers active in the American South in these decades. His clientele appears, for the most part, to have been the developing black middle-class population of the city (of which Roberts was a part): bankers, school teachers, social workers, and so on. Roberts’ work was rediscovered in 1977 and many of his photographs were published in a book, A True Likeness: The Black South of Richard Samuel Roberts, 19201936, in 1986 [1]. His images were considered significant for the way in which they represented African Americans – as middle-class, fashionable, self-assured, and free of the stereotypes that were imposed on black people in other representations. This appears to have been one of the reasons that Palmer was drawn to these photographs. He began painting from them in the 1990s.

Palmer’s source for Wanting To Say I was a photographic statement of black, middle-class selfhood. His treatment of that source allows its initial purpose to linger, while also transforming it into an image that speaks in much broader terms. The photograph is not a painstaking copy, and the process of painting presents the woman in a particular way. Palmer used this source on at least one other occasion, and you can compare her very open, resonant gaze in this work with the way she is presented in Our Dead (1993) where her narrower eyes create a sense that she is on edge and uncomfortable [2]. In his intentional and repeated reinterpretation of his photographic sources, Palmer’s process has been described as ‘a retrieval, a restoration, a memorialising, of the lost nameless’; it is an active engagement with a black history that is both visible and present, but also distant, due to the anonymity of the sitter in the photograph [3]. In response, Palmer’s very act of painting becomes a restatement of the selfhood that was first asserted in the original photographs and a restatement that allows this woman – who remains nameless – to become a means of activating and reflecting on black experience more generally, across time. She is lifted out of her specific context and is allowed to speak for not only that moment, but many others, before and after. The phrase from the title – wanting to say – seems to attest to this search for a personal and collective history through the anonymous photograph.

This sense that Palmer’s painting presents this woman as ‘on the move’, across time and continents, is underlined by the way she is framed – set back from the picture plane in this space that recalls the porthole of a ship. We are being asked to consider histories of migration here. In Britain, the post-war increase in migration is traced to the arrival of the SS Empire Windrush from the West Indies in 1948, and this continued during the 1950s and 1960s, despite increasing controls on immigration as time wore on. Palmer was part of this movement: he was born in Kingston, Jamaica in 1955, lived through Jamaican independence in the early 1960s, and arrived in Britain as a child in 1966 to live in Chelmsley Wood in Birmingham (there are several works by Palmer in public collections in the Midlands – two in Walsall and one in Wolverhampton) [4]. This experience of migration was far from unique, and not without trauma: his family was split up, as some members left first, in order to secure work and a home in Britain, before Palmer and the rest of his family could join them. In an interview, he has recounted how he cried throughout the aeroplane journey. His interviewer, Petrine Archer-Shaw, suggested that this migratory trauma presents a parallel with the forced migration of slavery, with journeys like Palmer’s amounting to a kind of ‘second crossing’ of the Atlantic [5]. In this way, too, the experience of migration becomes something that links black experience and black histories across time. Palmer’s recovery of the traumatic memory of his own journey inevitably recovers other memories – in particular of slavery, and the ruptures in memory and time that it provoked.

The complex processes and implications of black memory are particularly important to understanding the questions raised by Wanting To Say I; they were also themes that informed understandings of black experience in art and culture in the 1980s and 1990s, both in Britain and internationally, and continue to do so today. In Britain, the BLK Art Group (made up of Keith Piper, Marlene Smith, Eddie Chambers, and Donald Rodney) organised the First National Black Art Convention at Wolverhampton Polytechnic in 1982, and this has been considered a foundational moment in the development of the British Black Arts Movement, with which Palmer is associated. Questions of identity and its history were embedded in the work of many of these artists. The cultural and social theorist Paul Gilroy interprets this turn to history and memory as a response to ‘a present which places little value on either history or historicity’ [6]. Gilroy was examining in particular the writings of novelist Toni Morrison, who, reflecting on her 1987 novel Beloved, puts it more viscerally: ‘The struggle to forget which was important in order to survive is fruitless and I wanted to make it fruitless’ [7]. A return to the trauma of the past is necessary in order to contest a history that continually excludes black people.

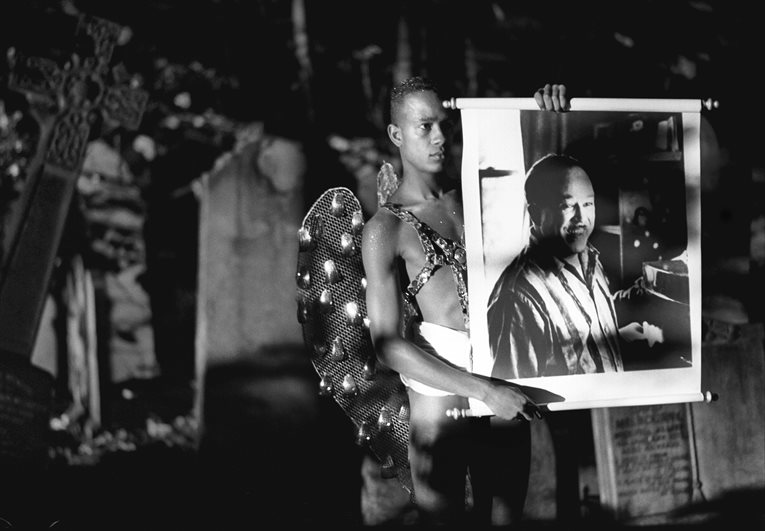

Fig.2 Isaac Julien, The Last Angel of History (Looking for Langston Vintage Series) (1989/2016), Kodak Premier print, Diasec mounted on aluminium, 180 x 259 cm. Courtesy the Artist and Victoria Miro, London and Jessica Silverman Gallery, San Francisco. ©Isaac Julien

If memory can be traumatic while serving a necessary political role, it can also create productive, vital connections across time. Palmer was not the only black British artist to reach back to the period of the Harlem Renaissance for his art. The artist and film-maker Isaac Julien turned to another figure from that era – the writer Langston Hughes – for his 1989 film Looking For Langston. The film is a poetic and impressionistic meditation on Hughes, which utilises some acted scenes and vignettes as well as, like Palmer, found material from the past, including newsreel footage, radio recordings, and photographs. José Esteban Muñoz has written about the powerful use of portrait photographs by Julien in his film, and his ideas can speak to Palmer’s own appropriation and re-presentation of the photographic portrait in his painting. Muñoz hones in on Looking For Langston’s opening panoramic shots, which include the image of a black angel standing in a cemetery and holding two photographs, of Langston Hughes (fig.2) and James Baldwin. For him, this is a powerful reinsertion of black (and queer) presences into a history that has excluded them, through the portrait; quite simply, it is a gesture that ‘first gives face, then gives voice’ [8]. Portraiture is allowed here to not just record and capture a presence, but also to resurrect and retain it. It allows you to imagine and visualise a past that can speak to and maybe begin to change the present moment.

This sense of memory – as working to contest history but also to imagine and write it – is crucial for Wanting To Say I. Palmer evokes black histories of movement and migration through the way he frames this portrait, placing this woman in movement across time, as both a reflection of the dislocation and loss of these histories as well as the connections and survival forged through diaspora. In addition, the way in which the form of this work suggests both a Renaissance tondo and the hull of a ship allows Palmer to situate his image in the European tradition that had excluded him while underlining the very historical fact of his exclusion. Memory, here, is both potentially traumatic (evoking slavery and the uprootings of migration) and potentially world-making (evoking connections and resonances between black subjects across time and space). It is crucial, I think, that Palmer, in his presentation of the portrait in this tondo/porthole composition encourages an awareness of looking: our look at her, and her look, back to us. In the history of western art, it is still relatively rare to find a representation of a black figure that returns our gaze – black people are, all too often, represented to be merely looked at. In Palmer’s work, however, this woman – financially secure, well dressed, confident – looks back, defiantly, to us. This is a visual connection, forged across time, that is intended to be unsettling, perhaps even traumatic, but also a moment of recognition.

About Gregory Salter

About Gregory Salter

Gregory Salter is a Lecturer in Art History at the University of Birmingham.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements

My thanks to Julie Brown at The New Art Gallery Walsall for the opportunity to view this painting and related material on the artist.

Endnotes

Endnotes

[1] Richard Samuel Roberts, A True Likeness: The Black South of Richard Samuel Roberts, 19201936 (Columbia, South Carolina, 1986). On Richard Samuel Roberts, see Eddie Chambers, Black Artists in British Art: A History Since the 1950s (London, 2014), p.84.

[2] This painting is in a private collection. It is reproduced in Chambers, p.82.

[3] Michael Phillipson, catalogue essay in Eugene Palmer: Recent Paintings, exhibition catalogue, Duncan Campbell Fine Art (London, 1999), np.

[4] Morgan Quaintance, ‘Studio Visit: Eugene Palmer’, radio programme, broadcast on Resonance 104.4FM on 17 May 2015 https://studiovisitshow.com/2015/05/17/eugene-palmer/ accessed 5 September 2017.

[5] Petrine Archer-Shaw, ‘…conversations with Eugene Palmer…’ in Eugene Palmer: A Norwich Gallery and Iniva Touring Exhibition, exhibition catalogue, Norwich Gallery, Norfolk Institute of Art and Design (Norwich, 1993), p.10.

[6] Paul Gilroy, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness (London, 1993), p.222.

[7] Quoted in Gilroy, (1993), p.222.

[8] José Esteban Muñoz, Disidentifications: Queers of Colour and the Performance of Politics (Minneapolis and London, 1999), pp.57–74.