Regional Galleries and their Hidden Histories

PhD student Elizabeth Lamle explores the migrant history and interpersonal relationships of the Garman Ryan collection at The New Art Gallery Walsall. With a focus on the unique connection between Rabindranath Tagore and Lucian Freud, she discusses how the display of this collection highlights the interconnected nature of émigré networks, and their role in shaping the production, acquisition, and display of artworks.

- Elizabeth Lamle

- Collection: Garman Ryan Collection: The New Art Gallery Walsall;

- Download a PDF [280 KB] of this article

- Keywords: Jacob Epstein, Kathleen Garman, Lucian Freud, Rabindranath Tagore, Dartington Hall

Nestled in the heart of the rural district of Walsall stands an imposing, iconic figure of cement: The New Art Gallery Walsall. Designed by Caruso St John architects, this new build, with its cavernous, stark interior – both impressive and intimidating, particularly in contrast with the surrounding regional market town – houses a surprisingly domestic-scale personal collection of art: the esteemed Garman Ryan collection, which this year enjoys the 50th anniversary of its formation. Finalised in 1973, this collection finds its roots in personal histories and the diversification of the art market. While it may surprise some initially to find a collection of this breadth and calibre here (with paintings, sculptures, and objects from Europe, Africa, Asia, and South America), viewing these works in the Black Country makes sense, as the demographics of Walsall have been shaped by migration for many years. The Black Country has the largest Punjabi community in England outside of London. Indian migrant workers have come to Walsall since the 1930s to work in the manufacturing and textile industries. Many African Caribbean migrants also came to Walsall to help rebuild the country after the Second World War, working to support the NHS and the transportation sector.

Understanding the international origins of the works in the Garman Ryan collection, the migrant history of both the collectors and the artists in the collection, and the surrounding migrant links with the local community, give a unique perspective of the collection. This article therefore aims to explore the émigré individuals and networks that are present in this collection. It demonstrates how both have played a critical role in shaping the production, acquisition, and dissemination of these artworks. In particular, this article seeks to highlight how the collection and its display offers insight into these networks and makes them visible to us.

Migration and interpersonal relationships are at the heart of this collection: Kathleen Garman (1901–1979) and her lifelong friend, Sally Ryan (1916–1968), worked together to assemble these objects over the course of fourteen years. The catalyst for this is said to be the death of Garman’s husband, the artist Jacob Epstein (1880–1959), who either collected or created most of the artworks in the Garman Ryan collection. Epstein was born in the United States, but relocated to Europe in 1902, where he initially married Margaret Dunlop (1873–1947), but then met and began a lifelong relationship with Garman in 1921. He also met Sally Ryan in London, where she became one of his students, as she pursued her own artistic career as a sculptor. While Epstein’s migration journey ended with obtaining British citizenship in 1910, his parents migrated further still: Max Epstein, formerly Jarogenski or Jarudzinski, and Mary Epstein, née Solomon, were Orthodox Jews from Augustów, Poland. As is shown in the diversity of the objects in the collection, Epstein’s interest in internationalism is evident throughout the collection and in his own works. Epstein was an American-British sculptor who was avant-garde in both concept and style. Abandoning classical Greek aesthetics, he instead drew inspiration from both European and more diverse art, such as from India, China, West Africa, and the Pacific Islands. And so when he collected a diverse array of objects and sculptures from across the world, it was not merely with an eccentric collector’s fancy, but rather through the eye of an inspired professional artist.

Epstein passed away in 1959; Garman was the sole inheritor to his estate, and that same year she began to form the collection. She sold much of what he had owned in accordance with his wishes. Two hundred plaster casts were donated to the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. His collection of ethnographic works – made up of over one thousand objects, it was one of the largest in the world to exist in a private collection – was broken up and sold at auction. Many key works were bought by the British Museum. While this was a substantial amount of sold or donated artworks, Garman kept those that were more personally significant. This no doubt explains the large presence of Epstein in Walsall’s collection: not only are these the objects that remained due to more personal links, but much of the collection is made up of Epstein’s own work – sculptures of himself, family, and friends. Bringing this sense of the personal to the public is what grants the Garman Ryan collection a certain intimacy and accessibility that otherwise would have been overwhelmed by the sheer size of the artist’s original collection. Many of the remaining pieces are also by family and friends of the couple, such as by the artists Augustus John (1878–1961), Henri Gaudier-Brzeska (1891–1915), Amedeo Modigliani (1884–1920), and Lucian Freud (1922–2011). There are also a number of works by Theodore Garman (1924–1954) who was the son of Garman and Epstein.

Garman’s intentions for the collection were unique. As the gallery states: ‘Though Kathleen spent the majority of her adult life in London, she wanted to gift her collection to the Black Country, believing it was important for culture to exist outside of the capital’ [1]. While collections of this calibre have long-been associated with London-based institutes like the Royal Academy or private collections, it makes sense that Garman would find the home for her collection outside of the capital and effectively contribute to the decentralisation of art in Britain. Garman grew up in Wednesbury, a town local to Walsall. And while much of the art market in England (still) converges around London, which Epstein would have experienced as both an artist and art collector in his lifetime, the artist also found his roots elsewhere. As noted, he demonstrated his passion for the international through both his collection and own artwork. Firstly, the display of the collection was designed by Garman to reflect Epstein’s interests: artworks are arranged within various themes, from animals, birds, children and figure studies, to flowers and still lifes. World objects also feature, as do the themes of work and leisure. The intention of these themes is to allow the viewer the opportunity to make unexpected links and comparisons across different time periods and countries, rather than in a more traditional chronological order, underlining the collection’s relationship to migration and transnational connections. Innovatively, the gallery does not separate the artworks in terms of object hierarchies. So, for example, both fine art and applied art and craft objects appear alongside one another. In the portraits room, you can find a sixteenth-century painting by an unknown artist of Corneille de Lyon (c. 1500/10–1575), next to the nineteenth-century Degas painting, Portrait of Marguerite, the Artist’s Sister (c.1856). The animals and birds room has a bright blue coloured lithograph of Birds in Flight (1953–1955) by Georges Braque (1882–1963). Braque’s work is featured alongside that of Eugène Delacroix, Egyptian and Māori artefacts, as well as Jacob Epstein’s sculpture of his Shetland sheepdog, Frisky. This interconnectedness of objects and artworks is clearly articulated though the display not foregrounding ‘western’ iconography above ‘non-western’. Instead of showcasing indigenous art as examples of ‘spiritual’ or ‘primitive’ work, therefore, The New Art Gallery Walsall’s display is far more egalitarian. Although works such as Moche (Pre-Columbian Peruvian) Vase in the form of a head (c.400–600 AD) are behind glass cases, this is due to both limited space and the necessity of conserving the works, rather than being treated as if they were objects in a ‘cabinet of curiosities’, or separated from more ‘modern’ sculptures. Indeed, the integral position of the Moche vase within the collection is reinforced by the adjacent figurative sculpture, Seated Boy (1948) by the Austrian sculptor, Georg Ehrlich (1897–1966).

A highlight of the collection that reflects its interconnected international nature is the Mask of Rabindranath Tagore (fig.1), a bronze sculpture by Epstein that can be found in the portraits room. Tagore (1861–1941) was a Bengali polymath of many disciplines: a poet, writer, composer, philosopher, painter, and social reformer. The sculpture recently stands out as one of the gallery’s choice works to celebrate the 50th Anniversary of the collection; not only as a key sculpture and figure of Epstein’s admiration, but also because it gestures towards how local communities have engaged with the collection. According to the Collections Curator, Julie Brown, it particularly caught the imagination of a group of women from the Aaina centre of Indian origin, with whom the gallery is exploring their collections as part of the ‘A Sense of Place’ project. This project engages with local and diverse communities. The role of a gallery in community engagement can work productively by acting as a place for people to visit and view materials from diverse cultures. In addition, it can spearhead projects for community integration and investigating local histories. The Garman Ryan Collection functions similarly, using its reputation to draw visitors to view not only works in the collection, but also other, more community-based exhibitions and projects that are being produced by the gallery. For example, the gallery recently hosted The Exiles exhibition (11 November 2022–5 February 2023), comprising a series of photographs by the contemporary artist, filmmaker and storyteller, Billy Dosanjah, which paid tribute to male migrant workers from the British colonies of South Asia, who came to the Black Country in the 1960s. Dosanja drew from his lived experience as a child of a migrant family, using ‘stories told by his family and community to explore what happens when cultures merge and to create a visual vernacular for a history that has inextricably shaped our region forever’ [2]. The exhibition highlights facets of the permanent collection by illustrating the local history that comprised the fabric of where Garman grew up and, ultimately, wanted to give back to, with the express interest of encouraging multicultural interconnection.

![Bronze head of a middle-aged man with a long beard and eyes wide open. He has a furrowed brow and hair down to his collarbone.]](/media-library/research/midland-art-papers/midland-art-papers-6-walsall-fig1.x8a90e114.jpg?q=80&f=webp&w=1440)

Fig.1 Jacob Epstein, Mask of Rabindranath Tagore (1926), bronze sculpture © The Estate of Sir Jacob Epstein. The New Art Gallery Walsall: 1973.082.GR.

Image courtesy of The New Art Gallery Walsall.

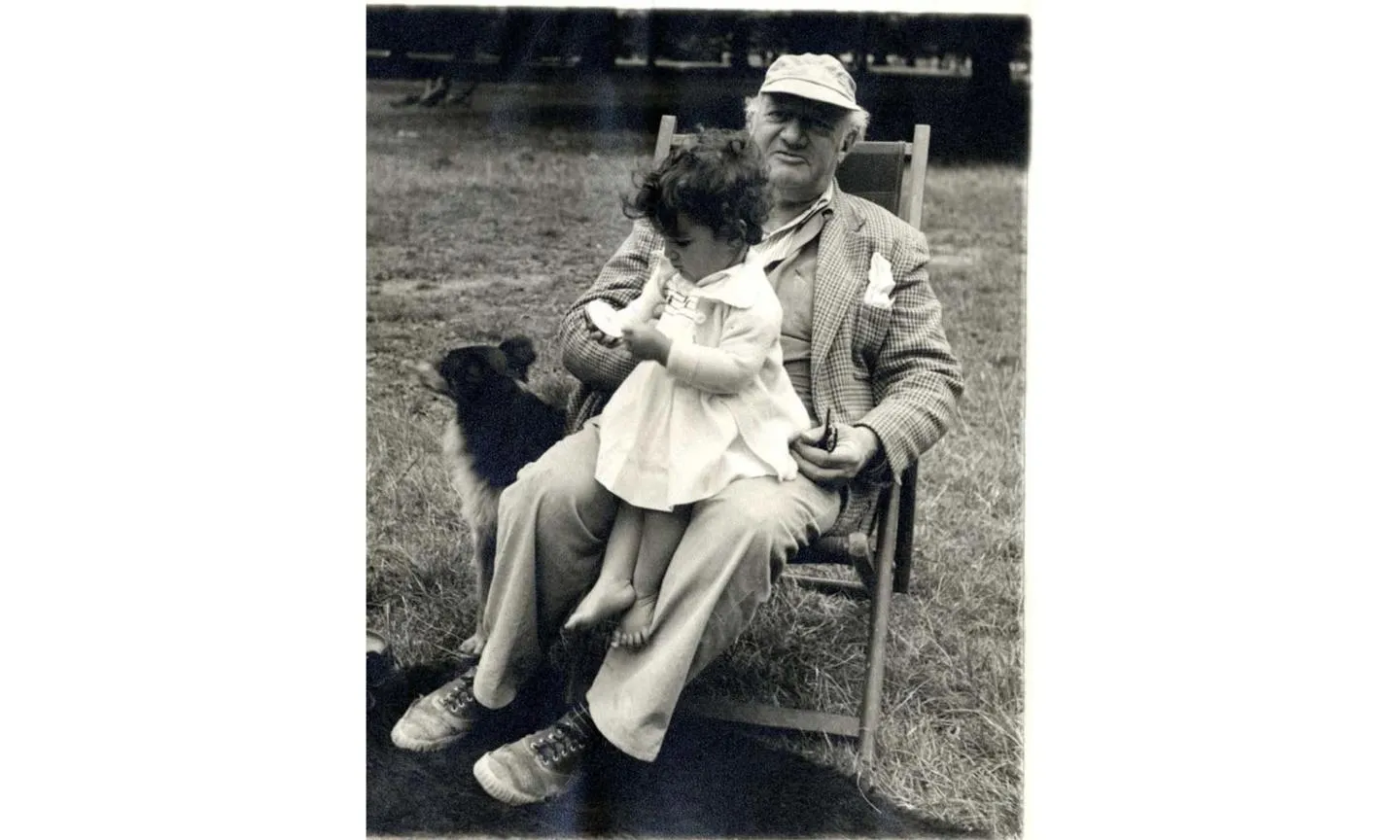

The Tagore bust also has a specific and historically important connection to another key artist in the collection: Lucian Freud (1922–2011). His painting Portrait of Kitty sits opposite the bust in the portraits room. While a visitor to the gallery might be surprised by some of the names of well-known artists in the collection that one might otherwise think hard to find outside of London or large institutions in major cities – such as John Constable (1776–1837), Edgar Degas (1834–1917), Henri Matisse (1869–1954), Claude Monet (1840–1926), Pablo Picasso (1881–1973), and Vincent Van Gogh (1853–1890) – Freud’s works are not included because of their reputation or quality. Rather, they were acquired because of his personal relationship with Epstein and Garman. In 1948, Freud – not yet bearing the reputation of one of Britain’s foremost portrait painters of the twentieth century – met Kitty Garman (1926–2011), the daughter of Epstein and Garman. Together, they had two children, Annie and Annabel Freud. There are only a few works by Freud in the collection and those are all personal in nature: paintings of his children, such as the oil painting Annabel (1967) and the watercolour painting Sleeping Girl (1960–62), both on display in the children room. There are also other photographs relating to Freud in the gallery’s archive, which give personal ‘behind the scenes’ looks into the family life. For example, photographs of Freud with various members of the family like the black and white photograph of Kathleen Garman and Lucian Freud (c. 1966) (fig.2). There is also a unique hand-drawn illustration, Encore (2003), which has been carefully cut out and saved from a personal letter by Freud [3]. Creation of and access to material like this was only possible because of his involvement in Epstein’s close network of family and friends. Freud’s presence in the collection, through his relationship to the collection’s founders, is endearingly encapsulated by the archive photograph of Epstein with his granddaughter Annabel Freud (fig.3). Keeping the display of these Freud artworks and other artworks relating to the family within these smaller wood-panelled rooms of the gallery – quite unlike the more common ‘sterile’ white cube display – leads one to imagine how they could have been on show around the family home. As well as tracing broad familial connections in the collection and museum, the display and architecture also invites visitors to make their own familial links when they enter into this space.

Fig.2 Unknown photographer, black and white photograph of Kathleen Garman and Lucian Freud (c.1966). The New Art Gallery Walsall Archive: BL/7/2/36/1.

Image courtesy of The New Art Gallery Walsall.

Fig.3 Unknown photographer, black and white photograph of Jacob Epstein seated with granddaughter Annabel Freud on his lap (c.1953). The New Art Gallery Walsall Archive: BL/7/1/1/11.

Image courtesy of The New Art Gallery Walsall.

The benefit of displaying the collection’s works in these themed rooms to create international and intergenerational links is demonstrated persuasively when one examines the connections between the works of Lucian Freud and the bust of Tagore. Freud’s relationship to Tagore finds its roots in Freud’s migration to Britain. Like Epstein’s parents, Freud was a Jewish refugee. He was born in Berlin in 1922 to parents Ernst and Lucie Freud, and as the grandson of the famous psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud. With the threat of the Nazi regime already impacting their community, Ernst Freud travelled to England in the summer of 1933 with the intention of migrating his family to safety there. He explored London as a potential destination for the family, while they remained in Berlin. And then when Lucie and the children moved to Britain, Ernst went back to Berlin to organise things such as the delivery of all of their belongings [4]. Lucie and the children’s first port of call was Dartington Hall – an estate in the rural English countryside that functioned as both a boarding school and progressive communal utopia.

Dartington Hall was built on the ideals of Rabindranath Tagore. One of the founders, Leonard Knight Elmhirst (1893–1974) had worked with Rabindranath Tagore in 1921, when he had helped Tagore set up the ‘Institute for Rural Reconstruction’ – later known as the ‘Abode of Welfare’ – in the Indian village of Surul. Disillusioned in the wake of the First World War, Elmhirst worked with Tagore’s teaching and spiritual philosophies. He saw a solution in the oversimplified binary of East versus West; as the French writer and art historian Romain Rolland explained this concept, people saw ‘the West representing science and materialism’ and ‘the East spirituality and the search for transcendence’ [5]. As Anna Neima argues, the Eastern spirituality that Leonard would base his work on was ‘a construct created not only by Orientalist Europeans, but also by spiritual teachers from Asia, including Rabindrananth Tagore, who sculpted their message in a way that they hoped would gain traction in the West. It was this rather vague form that many at Dartington looked to Eastern religion as an alternative spiritual framework’ [6]. The communal work at Dartington was therefore not simply a goal in and of itself, but also functioned to ‘find enlightenment’ by a ‘blending of the sacred with the everyday.’[7] Practically, this did not mean that one had to abandon their religion and embrace a new one upon entering Dartington Hall; rather, the adherence to religious tenets was as religiously followed as the framework was strict; that is, not at all. As an amorphous blending of ideologies, it functioned more as spiritual guidance that informed a holistic approach in the development of each of Dartington’s many avenues of experimentation. Dartington Hall – an old, run-down mediaeval estate – became a collaborative community that would not only bring to life Elmhirst and Tagore’s concept for an ideal society, but also act as a site of experimentation for ways to further societal development in what they deemed as the ‘right’ direction. This would include cultural, agricultural, and educational progressive experimentation.

Lucian Freud’s formative years, during his period of integration in Britain, was heavily informed and influenced by the progressive and educational philosophies of Tagore. Finding this connection highlighted within a gallery display is particularly poignant: Freud, by the allowance of the teachers at Dartington Hall, was not required to attend classes at the boarding school. And so, as a young German refugee who struggled greatly with the English language, he spent all of his school time either at the stables with the ponies, or attending only one class: art. This began a pattern of behaviour, where Freud would only attend – or seriously engage with – his studies in art. This continued in his next school, to the point where his father, exasperated with trying to get Freud to conform to more standardised regulations of education, eventually came to the conclusion that, if Freud was only going to participate in art class, then he might as well go to art school [8]. Freud was then sent to the Central School of Art and his career as a painter took off from the lessons and connections he made there. Finding Freud’s artwork literally facing the face of Tagore – the man who’s progressive attitude to education likely facilitated his progression as an artist – really illustrates the interconnected web of the émigré network, and the role of collections like Garman Ryan in preserving these works and creating compelling narratives and otherwise unseen connections between artworks and artists.

From Freud’s interviews and biography, it does not seem like he would have been aware of the importance of Tagore’s philosophy in shaping his journey of migration, as well as his approach to art and education. And the connected history between these two historical figures is not yet highlighted in the collection or gallery itself. And yet, fifty years later, they have been brought back together so effectively in the portraits room of the Garman Ryan collection. This speaks both to the history of migration that has been embedded in both the objects, their display, and in Walsall more generally, both producing and reflecting the émigré and international networks that underpin regional collections and their hidden narratives.

Furthermore, Lucian Freud was not the only member of the Garman-Ryan’s network to attend Dartington Hall. The daughter of Lorna Garman (whom Freud had an affair with before marrying her niece Kitty) taught there alongside her husband (Julian David). Their daughter Clio, who recently worked with Julia Brown, the curator of the Garman Ryan collection, on an exhibition of her mother’s work, also studied at Dartington Hall. The British printmaker and artist Dorothea Wight also studied there. She founded ‘Studio Prints’ in London, working with her husband Marc Balakjian, an émigré artist who later became Freud’s printer. Balakjian wrote an essay in Freud’s catalogue raisonné on the artist’s prints. The New Art Gallery Walsall has works by Balakjian in their collection and an exhibition of these works, displayed in connection with the theme of migration, is currently in progress. And so we continue to see these networks feeding into both the collector’s interpersonal connections, as well as into the artworks and displays at the gallery – even when we, the artist, collector, and curator, may not initially be aware of them!

Elizabeth Lamle is a PhD student at the University of Birmingham. She studied for her MA in Art History and Curating at the University of Birmingham 2019–2021, and her BA in Fine Art: Painting at the University of the Arts London 2013–2016.

Endnotes

[1] The New Art Gallery Walsall, Collections Library, accessed 22 February 2023.

[2] The New Art Gallery Walsall, Billy Dosanjh, The Exiles, accessed 24 April 2023.

[3] Freud’s image.

[4] The migration of Lucian Freud and his family is a central focus within this author’s ongoing PhD project, working with key letters written by the family that are now held in the National Portrait Gallery archive. An initial examination of these letters, as well as of Lucian Freud’s early childhood drawings, is available as a chapter in the forthcoming publication by the Research Centre for German and Austrian Exile Studies.

[5] Anna Neima, Practical Utopia: The Many Lives of Dartington Hall (Cambridge University Press, 2022), p.64.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ernst Freud, Letter to T. F. Coade, c. December 1938 – January 1939, Freud Museum Archive, LF/01/064.